Thought experiments are “devices of the imagination used to investigate the nature of things.”

Anytime you say “imagine” or “what if” and let your mind explore an idea you’re conducting a thought experiment.

It’s a classic tool used by great thinkers across many disciplines, such as philosophy and physics, to examine what can be known. Thought experiments enable us to explore impossible situations, evaluate the potential consequences of our actions, and re-examine history to make better decisions. Mastering thought experiments help us learn from our mistakes and anticipate (and prevent) future ones.

The goal of a thought experiment is to encourage speculation, logical thinking and to change paradigms, by demonstrating gaps in our knowledge and helping us recognize the limits of what can be known.

“Our own ideas are more easily and readily at our disposal than physical facts. We experiment with thought, so as to say, at little expense. It shouldn’t surprise us that, oftentimes, the thought experiment precedes the physical experiment and prepares the way for it… A thought experiment is also a necessary precondition for a physical experiment. Every inventor and every experimenter must have in his mind the detailed order before he actualizes it.” – Ernst Mach

Without realizing it, you’ve almost certainly used thought experiments to prepare for a complex task or to think creatively – rehearsing a difficult conversation, planning a piece of work, figuring out the cooking process of a meal.

Nikola Tesla used thought experiments to test and work out his ideas. Those that failed in his mind, he wouldn’t test physically, while those that were successful, he recreated exactly…with the same results as he had imagined.

The purpose of thought experiments

We can use thought experiments to test theories:

- To challenge (or refute) a prevailing theory, often using “reduction ad absurdum”

- To confirm a prevailing theory

- To establish a new theory

- To simultaneously refute a prevailing theory and establish a new theory

But we can also use thought experiments for practical purposes:

- Challenge the status quo and identify flaws in arguments (when dealing with misinformation or “fake news” for example)

- Explain the past (or try to)

- Examine how different choices in the past would have affected the present

- Ensure the (future) avoidance of past mistakes

- Predict and forecast the future (to think through second-order effects, for example)

- Working backwards to realize or avoid a particular future outcome

- To improve decisions by thinking through different opportunities

- To generate ideas and solve problems creatively, often when dealing with a bottleneck or constraint

Types of thought experiments

Thought experiments vary in different ways from one another, most of which are related to the flow of time.

Orientation in time

- Antefactual speculation: what might have happened before a specific event

- Postfactual speculation: what might have happened after a specific event

Direction of time: are we past-oriented vs future-oriented?

Sense of time: do we go forward or backwards in time?

Fom the past to the present or from the present to the past?

From the present to the future or from the future to the present?

Similar to the sense of time, we can also alter the sense of causality: do we go from cause to effect or from effect to cause?

More specific examples:

- Prefectual: speculate on possible future outcomes given the present.

“What will be the outcome if event E occurs?” - Counterfactual: speculate on the possible outcomes of a different past.

“What might have happened if A had happened instead of B?” - Semifactual: speculate what might have remained the same given a different past.

“Even if X had happened instead of E, would Y still have occurred?”- This type of thought experiment is often used in medicine.

- Hindcasting: run a forecast model after an event has happened to test the validity of the model’s simulation.

- Retrodiction: reverse-engineer a situation – going from the present to the past – to identify the ultimate cause of an event.

- Remember: the world is complex and often more than 1 factor is involved in shaping the present.

- Predictive: project circumstances of the present into the future.

- Backcasting: similar to Retrodiction but starting with an imaginary or desired future outcome, then working backwards to the present to identify how it can be achieved.

Thoughts experiments in philosophy and science

Philosophers use thought experiments to make theories accessible and spark new ideas in their quest to uncover the “truth” (about the world, about consciousness, etc.)

Scientists use thought experiments to develop a hypothesis or, like Tesla, prepare for experimentation in the physical world. With our current capabilities some hypotheses, such as string theory, cannot be tested. In this case, thought experiments allow scientists to develop a provisional answer, keeping in mind both Occam’s Razor and for it to be falsifiable.

Biologists often use thought experiments in a counterfactual way: why do organisms exist as they do today? Why are sheep not green so they would be better camouflaged from predators?

Surreal thought experiments like these help biologists, and us, identify gaps in our knowledge, deepen our understanding of the world and question the status quo.

Examples of famous thought experiments

Zeno’s Achilles and the Tortoise – Philosophy

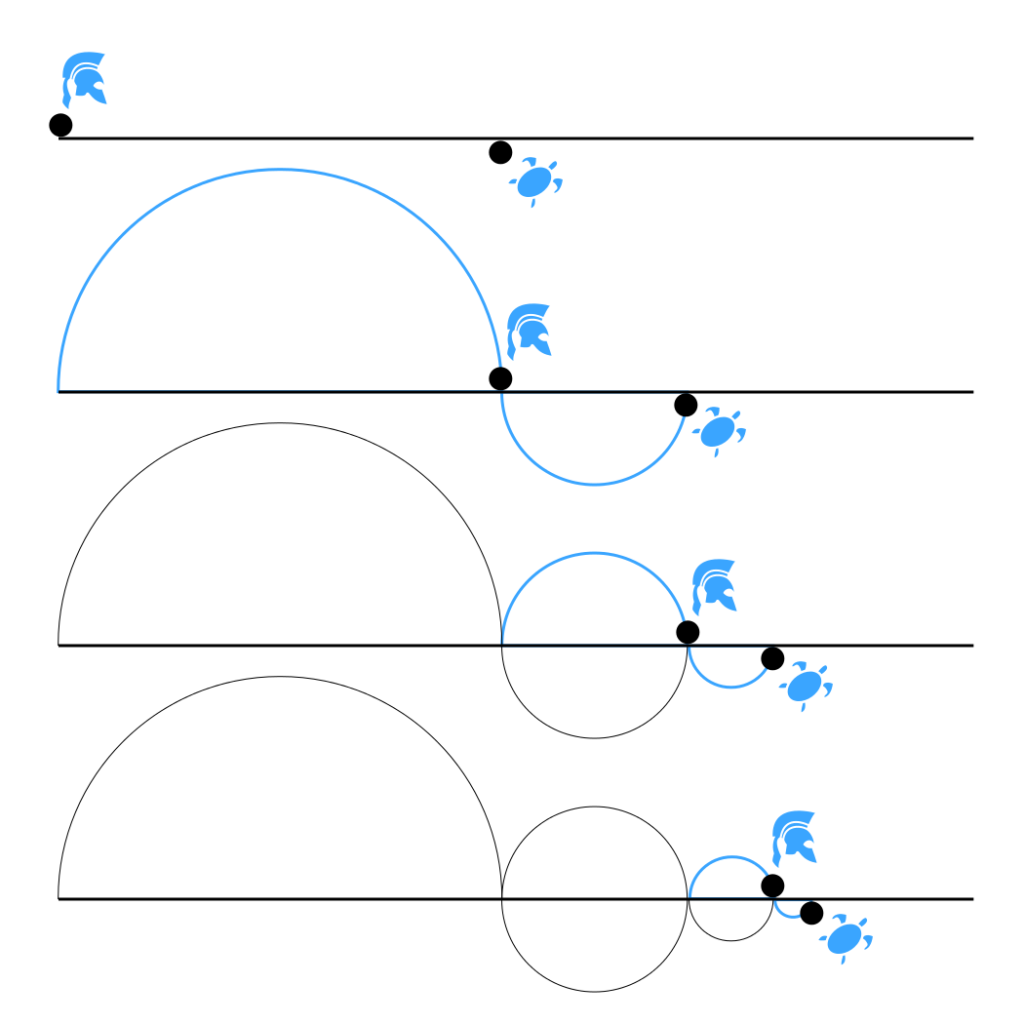

Achilles and a tortoise decide to race. Since Achilles is faster than the tortoise, he allows him a headstart. Both Achilles and the tortoise maintain a constant pace.

If you play out this race as a thought experiment, you’ll realize that Achilles will never catch up to the tortoise. Every time Achilles arrives where the tortoise has been, the tortoise will have pulled ahead. The distance between the two decreases, but they’ll never be in the same spot.

The below image by Martin Grandjean illustrates this thought experiment.

The Infinite Monkey Theorem – Mathematics

A monkey hitting keys randomly on a keyboard for an infinite amount of time will almost surely type any text, such as Shakespeare’s works. The probability that one monkey types Shakespeare’s Hamlet is extremely low, but technically not zero, as he types at random.

This thought experiment illustrates that any possible event, no matter how improbable, will eventually occur, given enough time. With enough random input (and time), anything can happen, including a drunk person opening his front door after many attempts.

Nassim Taleb wrote an entire book about the occurrence of improbable events. While we cannot predict what and when exactly something extreme will happen, know that an extreme event (both positive and negative) will eventually occur, given enough time.

The Trolley Problem – Ethics

Imagine a runaway tram. The driver has lost control. If it continues along its current path, it will collide with five people and kill them. You notice a switch which allows the tram to move to a different track where one man is standing. Do you press the switch to save five and kill one, or do nothing and watch the five die?

While this life-or-death thought experiment is theoretical, it has real world implications. For example, as we move to autonomous vehicles, would we want a car to swerve into a ditch to save a group of children but kill the driver or would we want the car to maintain its collision course?

How to do thought experiments

To make decisions: predicting the future accurately is impossible. Often we end up overthinking and delaying our decision. Instead of that, we can channel our tendency to avoid pain to improve the quality and speed with which we make decisions.

The simplest way is to focus on what Jeff Bezos calls “regret minimization”: “At the end of my life, will I regret not having done this?”

A “no” means it’s probably not worth doing. A “yes,” or even a “maybe,” tells you it probably is.

To reflect and improve yourself: at the end of the day, reflect on the things that didn’t go well and ask yourself “what might have happened if I had done/said…”

Either play out the scenario in your head or use this to brainstorm alternative approaches you can try next time you encounter this situation. You create your own feedback loop, accelerate your learning and ensure progress in a low-risk way.

To change your identity and habits: when you feel stuck in a rut, ask yourself “What if…” or “Imagine…” and visualize a desirable and positive future scenario. This can be about anything: your work, where you live, how you behave, how you treat others, how you treat yourself, etc.

Find 1 thing that you can do or replicate from your visualization right now and do that. Continue that cycle of visualizing and behaving/acting in that way, and you’ll find your reality moving closer to your desired one.