Summary

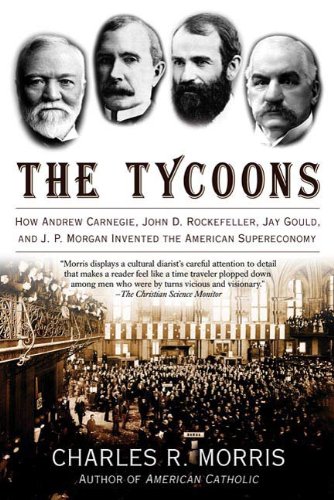

Great historical overview of Carnegie, Rockefeller, Gould and J.P. Morgan, their businesses and the times they lived in.

Key Takeaways

- Carnegie was a consumer of invention. He had the simplest of business mantras: cut costs, take share, gain scale.

- The classic Carnegie technique: focus on an objective, then cut brutally through any conventions, competitors, or ordinary people who stood in your way

- Gould focused on critical infrastructure.

- The characteristics Gould would display his entire career: the ability to tackle any endeavour, master any field, and, despite his frail constitution, to work prodigiously and push boundaries.

- A recurring pattern: exploit immature financial markets and then violently disrupt the comfortable business patterns of his competitors.

- Rockefeller was a great visionary and supreme manager, moved quickly and focused owning a large-scale distribution network.

- Fanatical attention to efficiency and costs.

- The characteristic Rockefeller methods: Move with shocking speed and minimum fanfare. Act with total confidence, but turn on a dime if new facts warrant.

- A typical ploy was to open his books to the target: any sensible man would understand that competition was hopeless and make a deal.

- He was not an innovator, but early adopter of technology and constantly on the lookout for talent.

- Rockefeller’s style was not to destroy good men or good companies but to enlist them in the cause.

- Morgan was the one overseas financiers trusted.

- Morgan’s genius was that of the disciplinarian, not that of the creator.

- There was no risk in his deals because he knew what he was doing.

- Improved infrastructure (Erie Canal, railroads) industrialized agriculture and so transformed an industry.

- Revolutions don’t boil up from a vacuum.

- How to (quickly) improve a country economically:

- Extraordinary quality of (American) workers

- Social fluidity of the industrial system

- Very high average educational levels

- Improve infrastructure

- Bonus: natural resources (harvested or acquired)

- “Airplane-seat pricing”: Almost all the costs of a commercial flight are incurred when the plane takes off, regardless of how many passengers are aboard. Since any additional revenue is almost pure margin, it makes sense to fill empty seats for almost any price at all, and airlines use elaborate pricing models that continually adjust fares to ensure maximum loading.

- The transformation of the food industry illustrates the daily disruptions of an accelerating boom.

- It is not the aggressive, efficient monopoly that is most to be feared. Far greater economic costs are inflicted by complacent, dead-weight, monopolistic incumbents.

What I got out of it

- Improve education and infrastructure, and a free, self-improving population will make the most of the opportunity.

- Read voraciously AND learn by doing.

- Learning shortcut: be an apprentice to a great mentor.

- Focus on creating a monopoly and controlling the bottlenecks in a supply chain or industry. Contract, outsource or partner for everything else.

- As an owner:

- Be the top salesperson

- Know your figures (revenues, costs and profit margins)

- Be frugal

- Constantly upgrade technology (which you can do if you know your figures)

- Have a network of information (people or travel)

- Grab any talent you find, when you find it

Table of Contents

Summary Notes

Preface

Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Gould tapped into the national predilection for speed, the obsession with “moving ahead,” the tolerance for experimentalism, to create one of history’s purest laboratories of creative destruction. Most businessmen of the time believed in orderly markets and gentlemanly fair profits, but these three came with flaming swords.

Morgan was the regulator, always on the side of reining in “ruinous competition,” most especially of the kind regularly unleashed by the other three.

Carnegie commenced his career of disruption. He was no technologist, but rather a masterful consumer of invention. His plants were always the biggest, the most automated, the most focused on pushing prices down. He had the simplest of business mantras: cut costs, take share, gain scale. Profits would take care of themselves.

Gould’s arena was railroads and the telegraph, the critical infrastructure of the period.

Rockefeller may have been the greatest visionary and the supreme manager:

he took over world oil markets so quickly and effortlessly that it was over before most people noticed, even as he taught the world its first lessons in the power of large-scale distribution.

Morgan, the most traditional figure of the four, was the one American whom overseas financiers trusted.

In America, no field offered opportunities as unlimited as business. America’s radically different manufacturing culture, its cult of the innovative entrepreneur, its obsession with “getting ahead” even on the part of ordinary people, its enthusiasm for the new—the new tool, the new consumer product—were all unique.

Prelude

On the Brink

The Pennsylvania fields were the largest yet discovered, by a huge margin, and within just a few years would supply the illuminating oil for almost the entire civilized world. With stakes like those, the nascent railroad wars would be fierce, often violent, and in a world with no system of law for controlling large corporations, deeply corrupting.

By war’s end, some three-quarters of New York’s farmers within wagon distance of a railroad depot were efficiency-minded middle-class businessmen running commercial establishments producing wheat, timber, and dairy products for sale. The transformation of New York’s farms dated from the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, and accelerated with the spread of regional railroads in the 1850s. Within a generation, they had decimated New England agriculture, forcing a decisive shift to a manufacturing economy in that part of the country.

The farmers of the “Northwest” were about to give New Yorkers a dose of their own medicine, seizing control of the grain trade and forcing their eastern brethren to specialize ever more intensively in dairies and fruit orchards.

The Artisanal Eden of Abraham Lincoln

The pro-development tradition came easily to Lincoln. His political idol was Henry Clay, the great apostle of canals and American self-sufficiency. Lincoln had been a businessman himself, although not a very successful one. He was a tinkerer, had worked as a surveyor, and held a patent on a device for lifting flatboats over river shoals.

Lincoln’s fascination with invention permeated his political statements.

For generations, historians argued whether the Civil War was primarily about slavery or was rather a showdown between competing economic systems. More recent historiography has shown how deeply Republican antislavery was intertwined with the Whig prodevelopment project. Republicans took economic independence as a prerequisite for political freedom—essentially updating the Jeffersonian vision of independent yeomen for a commercial society.

But for decades, every development initiative was beaten back by the slave interest, since speeding the settlement of the West, or even investing in rail and canal systems, would inevitably increase the power and population of the free states. To Republicans, and to Abraham Lincoln, southern obstructionism was a piece of a conspiracy to crush freedom everywhere, not just for slaves. If southerners were allowed to extend slavery into the territories, the blights of hierarchy and aristocratic indolence would surely follow, driving out free labor.

The Republican social vision: If the government supported individual independence and education, and jump-started a commercial infrastructure, a free, self-improving population would make the most of the opportunity.

In the 1860s, it was the North’s social system that was unusual; most other societies, whether or not they legitimized slavery, were organized on the same hierarchical principles as the American South.

Lincoln was fully aware of the North’s uniqueness. His speeches emphasize again and again the exceptionalism of America, where the broad populace enjoyed the social and economic underpinnings of political freedom. In no other country was political freedom an intrinsic part of the national project.

Young Tycoons

When Lincoln died, Andrew Carnegie was turning thirty, and already wealthy, although he had been a factory bobbin boy hardly a decade and a half before, and had yet even to settle on a career.

John D. Rockefeller was only twenty-six, but his Cleveland oil refinery was one of the largest and most profitable in the country, and he may have already formed his design of taking over the entire industry.

Jay Gould was twenty-nine, and after a brief, stormy career as a tanner, was trying his hand as a railroad turnaround specialist.

Pierpont Morgan was twenty-eight, quietly learning his trade within his father’s banking network.

Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Gould personified the unlimited entrepreneurial opportunities suddenly opened by America’s vast resources and its freedom from constraints of class and caste. For the man of fierce business ambition and massive talent, it was the one place, and perhaps the one time, where he could push as far as he could possibly go.

Carnegie

He was as relentless in self-improvement as in everything else, reading voraciously, and working hard on his accent and grammar. His life was dominated by his mother, Margaret, who imparted the fierce class consciousness of the respectable poor—a wrenching shame of poverty and withering scorn for the unambitious laboring people they were forced to associate with.

Andrew’s big break came when he was seventeen, in the person of Tom Scott, who became his business hero. Scott was one of the era’s great railroad executives.

It was the classic Carnegie technique: focus on an objective, then cut brutally through any conventions, competitors, or ordinary people who stood in your way.

Carnegie was so spectacularly talented — with his extraordinary intelligence and dead-accurate Scots practicality, his energy, his immense charm, his feline instinct for a deal — that he simply overmatched everyone else. He was also far better read than most of his peers, with an acquired, but genuine, taste for art and culture, and an attractive writing style.

The core fact about Carnegie was the drive to dominate — at all costs. But for some reason, although Carnegie was among the hardest of men, he always insisted on parading as a humanitarian idealist, as if his businesses were some kind of social welfare project.

Rockefeller

Perhaps in reaction to his father’s behavior, John was the most sober and industrious of young men — diligent at school, serious about his Baptist religion, scrupulously honest, utterly reliable. His adult life was similarly conventional, at least outside of business. He married young, was close to his wife and children, and in later years worked hard to prevent their lives from being completely distorted by his great wealth.

John was better educated than most young men of his time, completing high school and some commercial courses before starting work at sixteen as an assistant bookkeeper for a produce merchant in 1855. Two years later, with a loan of $1,000 from his father, John purchased a partnership in the firm of another merchant, Maurice Clark, a gregarious Englishman about ten years older than himself, and by the time John was twenty, he was already recognized as one of Cleveland’s outstanding young merchants—honest, reliable, and with a shrewd sense of commodity markets.

Rockefeller could demonstrate his extraordinary ability to combine headlong expansion with fanatical attention to efficiency and cost.

His direct, understated, factual style made him an exceptional salesman, and he must have exuded immense self-assurance. From the very start of his business career, he took enormous risks, but so calmly and matter-of-factly as to make them seem perfectly ordinary.

Even during his first years in refining, the characteristic Rockefeller methods were on full display: Move with shocking speed and minimum fanfare. Act with total confidence, but turn on a dime if new facts warrant.

A typical ploy was to open his books to the target: any sensible man would understand that competition was hopeless and make a deal. If a target was especially obdurate, rejecting all reasonable offers, a switch would finally turn and Rockefeller would suddenly unleash total, blazing warfare on every front—price, supplies, access to transportation, land-use permits, whatever created pain. When the target capitulated—they always did—the fair-price offer would still be available, often with an offer to join the Rockefeller team. It was industrial conquest on the efficiency principle.

Gould

Railroads became the center of Gould’s interests early in his career, and more than anyone else, he created the national railroad map that prevails to this day.

Gould’s mastery of financial arcana was paired with a strange streak of self-destructiveness. More than once, after a string of victories had left him in possession of the field, he would launch some new, seemingly pointless depredation that laid waste to everything he had worked for—as if launching stock wars was simply what he did. His reputation as a looter of his lines, however, is less fair. While he typically underinvested in his roads, he was always financially stretched, and over the years he probably put far more money into his roads than he took out.

Burning ambition more than made up for Jay’s lack of physical strength. He was essentially on his own from age thirteen, when his father registered him in a high school in a neighboring town and left him with a pile of clothes and fifty cents. Jay quickly found a job as a part-time, self-taught bookkeeper, and also proved an excellent student, with a genuine taste for literature, and a surprisingly mature writing style.

He taught himself surveying, and at seventeen he seems to have been the leading surveyor in the county, lobbying for the profession in the state legislature. He raised the financing for a comprehensive county map, which was a major undertaking, and along the way published a competent county history.

Failure though it was, the tannery episode highlighted the characteristics Gould would display his entire career: the ability to tackle any endeavour, master any field, and, despite his frail constitution, to work prodigiously; the constant pushing against boundaries and restraints; the impulse to expand in every direction at once, sometimes beyond all reason; the unfortunate habit of leaving a trail of dazed and battered partners in his wake; and the sharp reading of legal documents—one scholar has called him “probably the most successful litigant in American history.”

Morgan

Pierpont Morgan was already an experienced banker at the time of Lincoln’s death, having started and built his own firm during the war. Certainly, few young men had been as carefully brought up for their trade.

It was taken for granted that Pierpont would succeed to the firm. After the move to London, Pierpont attended a Swiss boarding school and then the University of Göttingen to work on his French and German.

There was no risk in the deal because he thoroughly understood what he was doing.

Pierpont was clearly well prepared. Endowed with a powerful intellect, great financial insight, and enormous personal forcefulness, he enjoyed a growing following on Wall Street, and was praised by Dun’s credit service for conducting a “first rate” business.

Morgan’s genius was that of the disciplinarian, not that of the creator. He was the last of the great eighteenth-and nineteenth-century merchant bankers, rather than the pioneer of a new dispensation. He did what his father and other bankers had always done, but in broader strokes, on a bigger canvas, applying his formidable intelligence to ever more complex financial constructions.

His fundamental drive was toward order and control, and he was appalled by the storm of “creative destruction” at the heart of the long American boom. He detested “bitter, destructive, competition” that always led to “demoralization and ruin,” in the words of Elbert Gary, the Morgan man at U. S. Steel. Often strangely inarticulate, as if rendered speechless by the titanic fulminations in his breast, he railed against the madness for progress and change that wiped out perfectly respectable businesses of perfectly decent gentlemen, against the gale winds of technology that turned economic assumptions upside down and made it impossible for his clients to pay their debts!

“…Glorious Yankee Doodle”

Rise of the Nerds

Blanchard perfectly understood that he had solved a general problem: how to machine any irregular shape at all. He produced prototypes for a host of items that previously could be produced only by hand labour—shoe lasts (forms in the shape of a foot, an essential tool for shoe and boot factories), axe handles, plow handles, and wheel spokes.

In a tour de force at the Paris Exposition of 1857, he executed a bust of Empress Eugénie entirely by machine. He also proved to be a pioneer in patent management, doggedly fighting off imitations and carefully specifying the applications and the permissible territory covered by each license. Over a long life, he was credited with dozens of inventions, in almost every field that caught his restless fancy, including steam engine and steamboat technology.

Revolutions don’t boil up from a vacuum. Blanchard’s invention was just one flowering of a unique concentration of machine-geek talent taking shape in the Connecticut River Valley, much as Silicon Valley emerged as a center of innovation a century and a half later. The fact that it happened along the Connecticut River, or happened at all, was, just as in Silicon Valley, the semi-random consequence of basic predispositions and happy chance.

Valley Guys

The attractions of the river valley started with its splendid endowment of physical resources.

- First, there was the prospect of almost unlimited power. The river’s fall across its entire length was greater than Niagara’s.

- Then there was direct water transport to New York harbour; the state of rural roads was such that overland transport longer than thirty to forty miles almost always cost more than shipping goods to New York from any point on the river.

- And finally, there were the convenient iron mines of Salisbury, Connecticut, just south of the Massachusetts border.

The military impetus behind interchangeability was the difficulty in finding skilled craftsmen to repair weapons in the field; but in the longer run, the precision methodologies developed under military contracts became a critical technology behind American manufacturing dominance later in the century.

They envisioned a manufacturing metropolis extending the entire length of the river, and their infrastructure investments benefited manufacturers of all kinds. A common strategy was to buy up stretches of the riverbank as mill sites, build a dam, some worker housing and amenities, then organize a textile mill and a machine company to supply the mill, often with a second round of investors, perhaps a successful mill manager putting up his life savings for the chance to own his own mill. The hope was that with anchor businesses in place, other entrepreneurs would lease the remaining mill sites, or “water privileges,” as the youthful Thomas Blanchard did.

The whirl of entrepreneurial activity in the Valley, the presence of the machine-geek culture, and the technical leadership of the Springfield Armory made it the natural center for the military’s development of interchangeability-level precision machining.

The Quest for the Holy Grail

John Hall was born into an upper-middle-class family during the waning days of the Revolution, and judging by his letters, was much better educated than Blanchard.

Although his work influenced almost every aspect of the post–Civil War manufacturing revolution, when he died he could fairly be considered a failure.

The credit for his great manufacturing innovations was accorded to Whitney and others.

The American Machine Tradition

Strict Armory practice came into full flower with the rise of America’s mass consumer society in the 1880s; indeed, it made it possible. Isaac Singer was a marketing genius who achieved world dominance for his sewing machine.

Although he did not manufacture to Armory standards of precision, he ran a well-organized factory system that served until about 1880, when sales soared past the 500,000 mark and Singer suddenly found himself in replacement-parts hell. At his company’s rate of growth, the world couldn’t supply the craftsmen to keep up with his service and repair requirements.

Most important was a style of problem solving. The fact that Americans typically thought of machine solutions as a first recourse, an integral part of almost any production process, was a major factor in the seemingly effortless move up to manufacturing scales previously undreamed of.

What Made America Different?

Modern scholars have considerably tweaked and refined Whitworth’s list. Scarcity of labour, for example, may have been a much more important factor in mechanizing midwestern farms than in, say, firearms production.

The abundance of natural resources undoubtedly channelled American technology toward wood, water power, and large farms, but the historian Nathan Rosenberg suggests it may also have affected the pace of mechanization. In deforested England, workmen had to be much more respectful of their wood supplies than Americans, who were prodigiously wasteful.

Almost all observers agreed on:

- The extraordinary quality of American workers

- The social fluidity of the industrial system

- Very high average educational levels

Key to the entire process was a consensus within the government and military that advanced technology was very much a national priority. Driving it all was the sense of opportunity—Lincoln’s “prudent, penniless beginner” could strive to become an independent businessman.

Bandit Capitalism

In a pattern he would repeat again and again, Gould took control of the Erie by exploiting immature financial markets, and then violently disrupting the comfortable business patterns of his competitors. The resulting price wars and frantic defensive investments helped force the all-out, lurching style of railroad development that characterized the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Railroad Privateer

“Airplane-seat pricing” is the reason a modern business traveller may find herself squeezed into a middle seat next to a grandparent who paid a fifth as much for the same ticket. Almost all the costs of a commercial flight are incurred when the plane takes off, regardless of how many passengers are aboard. Since any additional revenue is almost pure margin, it makes sense to fill empty seats for almost any price at all, and airlines use elaborate pricing models that continually adjust fares to ensure maximum loading. After fare regulation ended in the 1970s, prices plummeted, passenger miles soared, and most lines constantly skitter on the edge of bankruptcy.

The economics of railroads are the same as for airlines, and Jay Gould may have grasped them more quickly and clearly than anyone else. The favoured contemporary response to price wars was to form pools, or industry rate agreements, which inevitably collapsed because of cheating. Instead, Gould hoped to control pricing by establishing monopolies over natural regions of commerce.

Pennsylvania had actually been divesting its ownership interests in its western connections. Its executives prided themselves on keeping debt low, extending lines cautiously, and conserving cash. In the pre–Gould days, this was the epitome of good management; the railroad bosses were like peacetime generals who keep the troops fed and equipment working, but haven’t a clue about strategic manoeuvre or positional advantage.

In the summer of 1869, with his railroad wars raging on every side, and the outcome still hanging in the balance, Gould launched, or was swept up in, the infamous Fisk–Gould “Gold Corner.” It is one of the most notorious episodes in American financial history, one that demonstrates not only Gould’s own self-destructive streak but also the fragility of America’s postwar financial markets and the openness of corruption. The Gold Corner forever fixed the image of Gould as the evil genius of Wall Street.

The Gold Corner

The impact of the Gold Corner on the national economy was fleeting at worst, but it was devastating for Gould. Besides destroying his reputation, it delivered a knockout blow to his railroad strategy.

Ouster

The Pennsylvania’s escape from Gould’s nighttime assault marked the last step in the ascendancy of Tom Scott, who succeeded J. Edgar Thomson as president in 1874. Scott, in contrast to the conservative Thomson, was an exemplar of the railroad-president-as-buccaneer, violently wrenching his board away from its narrow inward concentrations into a near-reckless program of expansion and encirclement aimed at making the Pennsylvania America’s dominant national carrier.

From that point, the national railroad wars came to resemble the Chinese game of Go, in which players win points by outflanking and encircling an opponent’s positions. In the scramble for territorial advantage, new lines were spun out with abandon, far ahead of business demand.

The First Oil Baron

Standard Oil (as the Rockefeller refineries were rechristened in 1870) was not an innovator in any of these areas, but Rockefeller was an early adopter of proven technologies and constantly on the prowl for talent—buying up Charles Pratt’s cutting-edge refinery in 1874, for instance, and picking up the brilliant distillation specialist Henry Rogers with the deal.

There is evidence that Rockefeller was running very scared in this period, for he doubtless divined that the industry was on the edge of a cataclysmic shakeout. He pressed on every front to reduce costs, cut waste, and sell more by-products. No opportunity to pick up a nickel of margin was overlooked—creating his own hauling operation, building his own barrel plant, purchasing his own piping supplies.

The Muckrakers’ Case against Rockefeller

The loudest complaints about Rockefeller’s prices came from men who received less than they had invested. Today we would take that for granted, even for businesses that weren’t designated for the scrap heap. We assume that a new breakthrough, as in telecommunications or the Internet, will cause a burst of business formation, followed by a harsh consolidation as the victors emerge. Businessmen in Rockefeller’s era, however, placed a much higher value on stability.

Carnegie Chooses a Career

Carnegie’s companies were always high-quality, high-performance vendors, but his real edge came from Scott’s and Thomson’s inside positions.

Wrenchings

Supply Shock

As American productive capacity reached parity with, and then surpassed, Great Britain’s, the greenback and sterling realigned by themselves. Falling nominal prices signified strength, not prostration.

The roughly parallel developments in Great Britain suggest the power of the forces that were afoot. There was a British “Great Depression” starting in the 1870s, which lasted much longer than the contraction in America and which exhibited much the same dissonance between perceptions and the underlying data. As one historian put it: Prices certainly fell but almost every other index of economic activity— output of coal and pig iron, tonnage of ships built, consumption of raw wool and cotton, import and export figures, shipping entries and clearances, railway freight and passenger traffic, bank deposits and clearances, joint-stock company formation, trading profits, consumption per head of wheat, meat, tea, beer, and tobacco—all these showed an upward trend.

Yet just as in the United States, “an overwhelming mass of opinion…[agreed] that conditions were bad”—although “the wails of distress did not come from the mass of the people, who were for the most part better off, but mainly from industrialists, merchants, and financiers.”

The Birth of the Factory Farm

Bonanza farms were constantly evolving. The first generation of farms, for instance, were solely devoted to wheat—Dalrymple even imported the oats for the horses—and it took a while to learn the limits of extreme monoculture. The fact that the outsiders tended to be “book farmers” was actually helpful, for they hadn’t learned century-old lore at their daddies’ knees and were quick to reach out to agronomists for advice on seeds, fertility maintenance, and erosion.

A distinct corn belt also developed as the 1880s progressed. Wheat farming tended to drift westward— California was an important center by the 1890s—while corn stayed close to Chicago, since corn-fattening was the last stage in preparing cattle for slaughter.

The Disassembly Line

A rough parallel to the bonanza farm developed at about the same time in the meat industry. The Texas cattle ranch was born out of the devastation of the Civil War. Antebellum beef and pork production was distributed through the mid-Atlantic and border states and along the southern coasts from the Carolinas to Louisiana.

In the 1880s, Jay Gould extended a vast, more or less unified, railroad system through the Southwest, consigning the drive to the realm of the dime novel.

Eastern and European capital quickly flowed into large-scale ranching. Barbed wire may have been the essential invention, although careless attitudes by the federal government and railroad companies toward their land grants also helped —many ranchers simply took over vacant land with no pretence to title.

Meatpackers found themselves in the same catbird seat as oil refiners—controlling the bottleneck between a diverse and unorganized ranching industry and a widely dispersed consumer market.

Very quickly the industry consolidated into four major players—Swift, Armour, Hammond, and Nelson Morris, another Chicago slaughterer—with a few other firms, like Wilson or the Cudahys, holding the fifth position from time to time. Most of the firms expanded their holdings up and down the value chain, from stockyards and ranches to wholesale distribution centers as far away as Tokyo and Shanghai.

The packing house “disassembly” line, an inspiration for Henry Ford’s factories, became one of the lurid wonders of the world.

The costs of slaughtering and packaging fell sevenfold, even as the scale of operation opened up profit opportunities in byproducts. One of Armour’s very early investments was a glue factory, and all the houses expanded aggressively into hides, oils, and tallow. Hog processing was different in detail, but the pattern of development was roughly the same.

The transformation of the food industry illustrates the daily disruptions of an accelerating boom.

The prewar generation of eastern wheat farmers were also close to their markets and could understand, and to a degree anticipate, ups and downs in their customers’ behavior. But a mechanized monoculture grower on the Northwest plain lived in a much more volatile world: a shift of weather patterns on the Russian steppes could wipe out his year. Specialization and mechanization increased revenues and profits, but also multiplied the risk of catastrophic failure. Men who prided themselves on crop management burned late-night kerosene lamps puzzling over balance sheets. Times were good, according to the numbers, but the loss of control was frightening.

The packing industry is a case study in how industrialization was creating millions of jobs; by century’s end, meat packing was the largest industrial employer in the country. But that was cold comfort to the butchers and middlemen/wholesalers wiped out by Swift and Armour. Headlong modernization must have greatly increased the levels of frictional unemployment even as overall job numbers moved up strongly. The new jobs were in the wrong place, or were jobs that skilled tradesmen would never consider taking—at least at first.

Modernization also was very hard on small merchants. Meatpackers were not the only large manufacturers taking control over their own distribution and retail chains. Singer Sewing Machine is another early example. American radicalism typically bubbled up from the petit bourgeois, for they, not the oppressed poor, were often the first victims of modernization.

Most businessmen reacted with fear at the violent disruptions of the 1870s. Top of the food chain feeders saw only a world ripe with opportunity.

Mega-Machine

Seizing on the openings created by the 1873 crash, Carnegie, Gould, and Rockefeller all played primary roles in driving the scale shift—Carnegie the expansion in steel, Gould in railroads, and Rockefeller, who started with the cleanest slate, actually creating an entity that came closest of any to the perfect global machine of the metaphor. Morgan plied his trade as a banker, and would emerge after yet another market break in the 1880s as the regulator of machines that other people built.

Steel Is King

If you believed in America, you believed in railroads. And if you believed in railroads, you believed in steel. It was insatiable demand for steel rails by American railroads that made steel a mass production business and led to its gradual supplanting of iron for most industrial purposes.

The breakthrough to large-scale steel-making came in the 1850s from the prolific British inventor Henry Bessemer. Bessemer guessed that if he simply injected cold air into a chamber of molten iron, the oxygen in the air should, by itself, ignite the carbon in the iron and burn it off without puddling.

Bessemer had unwittingly started with an ore that was unusually low in phosphorus, which turned out to be the one type of ore his process worked with. It was twenty years before the phosphorus problem was solved by a Welsh iron chemist and his cousin, a police court clerk, who came up with a “basic” furnace lining called the Thomas-Gilchrist process that precipitated out the acidic phosphorus.

By that time, Bessemer’s process had a rival in Charles Siemens’s “open hearth” method. Siemens used a furnace similar to an iron puddler’s, but achieved the required superheating by recycling waste gas through a clever array of brick chambers. The process was slower than Bessemer’s, but many steel-makers thought it gave them better control.

Alexander Holley brought the gospel of steel to America. He is not much known now, but was important enough in his day that his statue, in full moustachioed glory, stands in New York City’s Washington Square Park. Holley was a physically impressive polymath.

King of Steel

Carnegie’s lifelong disdain for pools. He was happy to join them, and was vigilant in enforcing them when it was in his temporary interest to do so, and as freely violated them when they were not.

“When demand slumped, the firm with the newest equipment—it was often Carnegie’s—found that its losses were least (or those of its rivals most) when it reduced its prices so as to run fully occupied.”

The rise of Carnegie Steel was not based on any hidden advantage or technical edge. Carnegie was a relatively late entrant to the industry, and all of his American competitors used essentially the same Holley plants as he did.

The company’s competitive advantage, it appears, was mostly Carnegie—his relentless pressure, his hounding to reduce costs, his instinct to steal any deal to keep his plants full, his insistence on always plowing back earnings into ever-bigger plants, the latest equipment, the best technologies.

Other companies went through cycles of rise and decline, as founders got comfortable, shareholders demanded payouts, or good times allowed workers and managers to cruise a bit—as almost the entire British steel industry did after the great rail boom of the 1880s. But for twenty-five years Carnegie never let up.

Carnegie’s quasi-official role in the early years was as the company’s salesman, a job that he filled superbly.

The dual roles as primary owner and chief salesman gave Carnegie the ideal vantage point for tuning production and pricing, and evaluating the profitability of new investment. He understood the subtle absorptions of fixed costs that improve margins as production is pushed further out the curve of the possible.

Two courses are open to a new concern like ours—1st Stand timidly back, afraid to “break the market” [or] . . . 2nd To make up our minds to offer certain large customers lots at figures which will command orders—For my part I would run the works full next year even if we made but $2 per ton.

Since Carnegie traveled more than anyone else in the company, and was constantly on the lookout for new technologies, he was among the best informed people within the company on technical developments.

Gould (Almost) Conquers All

Most railroad men in Gould’s day understood that railroads were natural monopolies, since few localities generated the traffic to support competitive lines. The conventional solution was to enter into gentlemen’s agreements to respect preestablished competitive boundaries, dividing up the traffic in a “friendly” way. Such “pooling” arrangements became standard practice in the decade after the Erie Wars—watching Scott nearly run the Pennsylvania aground in his furious reaction to Gould’s 1869 onslaught was sufficient caution on the pitfalls of unrestrained competition.

Gould did not think like most railroad men. Like Carnegie and Rockefeller, he regarded pools as refuges for the weak, although useful for masking predatory intentions.

The solution for the fragmented state of the railroads was to consolidate, not to negotiate elaborate paper compacts. Roads that were willing to join his network would find him a fair purchaser; holdouts would find themselves under attack in the securities market.

Gould did most of the work himself. He had lawyers he relied on, and he regularly took counsel with Dillon and Sage, and often the cable mogul Cyrus Field

Like Rockefeller, Gould never jeopardized a good deal by trying to squeeze out the last penny of advantage.

Rockefeller’s Machine

There was one more high-profile struggle to be won, and it arose because Rockefeller, for once, had missed a beat on new technology. A group of entrepreneurs from the oil regions, led by one Byron Benson, started work on a seaboard pipeline, the Tidewater.

The Standard’s commitment to long-distance pipelines was the beginning of the end of the railroads’ dominant role in petroleum transport. Rockefeller began to negotiate what were effectively reverse-rebate arrangements, guaranteeing the roads minimum returns for maintaining their oil-shipping facilities whether or not he used them. The last step in achieving total industry dominance was to integrate backward into crude production, which took place gradually through the 1880s.

Running the Machine

A word on Rockefeller as a manager, for he has a claim to be not only the first great corporate executive but one of the greatest ever. He had the rarest of talents for adjusting to each new stage of the Standard’s growth.

Carnegie’s drive to the top of the steel industry feels almost hormonal—boundless energy, aggression, and ambition fortunately channeled into something constructive. Rockefeller’s seems much more a matter of sheer intelligence in pursuit of an ever-larger scale of elegance and order.

Carnegie pushed and badgered, shamelessly playing executives against each other, and too frequently crushed his best men, like Henry Frick. Rockefeller’s management style, by contrast, was quiet and reasonable, even though, unlike Carnegie, he never held a majority stake in the Standard. If he had the final word, it was because his very talented executives believed in their hearts that he was smarter than everyone else. He always reached out for the ablest executives he could find, gave them plenty of running room and support, and kept most of them bound to him for the rest of their careers.

Rockefeller’s style was not to destroy good men or good companies but to enlist them in the cause.

The First Mass Consumer Society

Department stores were the surface foamings of a tectonic reshaping of American social and economic arrangements that was gaining speed in the 1870s and 1880s.

The New Middle Class

The 1880s and 1890s saw a sharp ratcheting-up of reformist interest in public education, which was sustained well into the twentieth century. Much of it was prompted by the business demand for capable workers, and had a grimly functional tone—as in “the student should be able to quickly adapt to the rigours of the industrial assembly line”—and there was a conscious funnelling of immigrant and working-class children into manual training courses.

This same period saw the widespread introduction of the graded school—no more one-room schoolhouses—standardized testing, and minimum standards and certifications for teachers.

Middle-class values spread so fast in part because the status was attainable for almost any young person with energy and ambition.

Things

When railroad men and their investment banks adopted their “if you build it, they will come” strategy, they were not thinking of a consumer revolution: Gould, Vanderbilt, and Scott went to war over grain, iron, and oil freights, not corsets and ribbons. Pennsylvania managers, who took great pride in the high polish of their shipping and scheduling machinery, were unpleasantly surprised in the 1890s to find themselves ensnarled in a thickening maze of short-term hauling and small freights. Consumers were taking over, and there was considerable management foundering until the road learned to adjust.

Julius Rosenwald, who joined Sears in 1895 and assumed operational responsibility from a very in-over-his-head Richard Sears, was arguably the first retail management genius.

Professional entertainment—baseball, boxing, vaudeville, burlesque, Barnum’s circus, and the “Amusement Park”— were fixtures even in smaller cities.

Armory Practice Redux

The bicycle industry that fed the cycling enthusiasm of the 1880s and 1890s was one of the first where manufacturers understood the importance of Armory standards from the outset, and nicely illustrates the direct gene transfer from Valley practice to mass consumer manufacturing.

The “father” of the bicycle in America was Albert A. Pope, a Boston merchant who became infatuated with bicycles when he saw a British high-wheel cycle at the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition. He travelled to Europe, learned how they were manufactured, and returned to create a bicycle industry in America. Pope seems to have understood the opportunity for a mass production industry from the very start, because he was determined that, unlike the European products, his would be produced with “interchangeable parts,” an advantage he promoted in his earliest brochures.

A superb businessman and marketer, Pope bought up every American bicycle patent he could find and evangelized his cycles by financing bicycling magazines and sponsoring bicycle clubs, competitions, and trade shows. He organized local pressure groups, coordinated through his “American Wheelmen’s Association,” to demand better roads, and his bicycle posters, some by Maxwell Parrish, became popular artwork.

Anxiety

The flip side of American fluidity was status anxiety. The sure connections between one’s father’s place in society and one’s own, the reliable guides to behaviour so firmly attached to one’s station, were all gone. The psychological costs could be heavy.

Nineteenth-century America was the trailblazer for that virtuous cycle of consumer-driven growth, and it presented industrialists and financiers with an entirely new order of demands—to achieve ever-greater scale, but with much greater product varieties and to higher standards of precision. The technical challenge was one that few entrepreneur-managers were up to. To cope, companies had to assemble entirely new sorts of managerial and technical bureaucracies. The age of the consumer, that is, could not get underway except in parallel with the age of the corporation.

Paper Tigers

The Conquest of the Clerks

Economists say that bigger companies need paperwork to substitute for internal markets. It’s a nice point. In Lincoln’s era, an axe maker bought semi-finished wood and steel and sold the finished wares to wholesale merchants. As long as there were several suppliers and several distributors, he was reasonably sure of getting fair prices on both sides.

But life was much different for Carnegie Steel. By the 1880s and 1890s, it supplied its own coke and iron ore, its own pig iron, and much of its own rail and lake shipping facilities, and it maintained its own sales force. How, therefore, to compute profits on steel? First, one had to tot up the costs for the coke, the ore, the shipping, and everything else. But in the absence of normal invoices from outside suppliers, one needed careful internal cost records, which required an ever-growing army of clerks.

But economists’ explanations skip past the daily textures of business life.

At bigger scales and higher speeds, the little details became ever more crucial. No one understood this better than Alexander Holley, the guru of American steel-making.

You could not argue with Holley: he was widely acknowledged as the most deeply knowledgeable steel engineer in the country, was constantly travelling the world in search of best practices, and could fully document his recommendations. The whole course of his work was to force steel-makers out of their old rule of thumb operations into analysis-based management.

In the 1880s, however, Wall Street began to build a market in “industrial” securities, essentially shares in businesses other than railroads and banking. While public markets offered greater financing flexibility for big companies, they multiplied record-keeping and correspondence requirements. Ironically, it was that most inward-focused of companies, Standard Oil, that indirectly created much of the impetus for industrials in the first place.

The consolidation and scaling up of Holley-style continuous-process manufacturing businesses in the 1870s and 1880s—besides iron and steel, in oil, chemicals, flour, meat—eliminated many traditional craft categories. Labor historians sometimes speak of the “de-skilling” of manufacturing, which is not entirely accurate. It took considerable judgment and experience to be a senior operator in a high-speed rail rolling mill, and, often enough, the tasks eliminated were the most dangerous and exhausting ones, like hand-pouring molten steel into ingot molds.

The skills required in the modern factory were invented and controlled by the employer, and didn’t take years of apprenticeship to acquire. The same visitors were struck by the short training periods required for raw hands in American mills; one Carnegie executive claimed he could make a farmboy into a melter, previously one of the more skilled positions, in just six to eight weeks. Integrated operations also eliminated the last vestiges of internal contracting.

The Creation of the Carnegie Company

Schwab proved to be one of the greatest of American steel executives. He was a store clerk when he caught the eye of Captain Jones, and, at seventeen, started at the company as a dollar-a-day stake driver. Six months later, Jones had him running a major blast furnace construction program.

A fine picture of Schwab’s presidential style can be gleaned from the minutes of the weekly operating committees: he was crisp and decisive, deeply informed, and with an easy, collegial, command. The plant rank-and-file loved him; he was one of their own and a regular back-slapping presence on the factory floor, although he held the line on costs and wages as hard as Carnegie and Frick. He was also formidably self-educated in the technical aspects of steel-making and controlled the roadmap for technology investments. On top of all that he was a charmer and a jester, with just the touch of sycophancy that made him dear to Carnegie. Although Schwab stayed on good terms with Frick, his mere presence fed into Carnegie’s lamentable tendency to adopt one favourite at a time and make everyone else miserable.

Trust-Busting

Northern Securities culminated a long string of decisions that left no doubt of the Court’s hostility to “loose” combinations like Albert Fink’s railroad pools. You didn’t need a genius lawyer to figure out that if you wanted to combine, a genuine “tight” merger had the best survival prospects, as long as you merely stayed under a Standard-scale “unreasonableness” threshold.

Spotlight on the Standard

Its period of global monopoly ended when the formidable Nobel brothers opened the Russian Baku fields in the early 1880s, built railroads and pipelines into Europe, and patented refining technology arguably superior to the Standard’s. About the same time, Royal Dutch Shell made major new strikes in the East Indies and invested heavily in ocean tanker technology.

The sharp jump in earnings is perfectly consistent with the evidence that the Standard of the early 1900s was rapidly losing its competitive edge.

The political analyst Charles Ferguson has pointed out that it is not the aggressive, efficient monopoly that is most to be feared. Far greater economic costs are inflicted by complacent, dead-weight, monopolistic incumbents.

As the British had discovered to their grief in steel, it is almost impossible to maintain a technological edge amid declining production, and the huge new refineries and pipelines in Texas and California were inevitably a generation ahead of the Standard’s. By the time the breakup order was finalized, the Standard’s alleged “90% share” of domestic refining was closer to 65 percent and falling, while its position in other industry sectors was much lower than that. Worst of all, its central business premise was crumbling with frightening speed. The accelerating spread of electricity was clearly going to obliterate the kerosene market, and the company had been late to appreciate the opportunity in automobiles.

The Age of Morgan

Morgan was among the first generation of bankers whose clients were primarily private corporations instead of governments, but there were substantial continuities in approach. His mediations among the railroad barons were very much in the tradition of the supranational financial/diplomatic service operated by the Rothschilds and the Barings in midcentury Europe. Despite their occasional huge profits from war finance, the great banking houses detested war: the business disruptions were simply not worth it.

“Jupiter”

Unlike the sprawling bureaucracies of a modern bank, the Morgan bank’s power was also very personal. During Morgan’s career, there were never more than twelve or thirteen partners at any one time, nor more than about eighty employees altogether.

The bank’s high reputation in Europe was a key to its position in America. Europeans remained major buyers of American stocks and bonds throughout the nineteenth century, and clearly preferred paper with Morgan’s name on it. As Pierpont would have been the first to acknowledge, that respect was tribute to Junius’s many decades of solid, conservative banking performance. A signal indicator of the bank’s global stature came in 1890 when the Barings banking house nearly failed after a disastrous gamble on Argentinian bonds. With most London firms running for cover, the Bank of England turned to Pierpont to lead the Barings rescue: for nearly five years Morgan was effectively Barings’ receiver, making him an important player on the London exchanges.

Harriman came late to the railroad business, but by the turn of the century had emerged as one of the first of the great modern railroad executives.

The Reading restructuring was one of the first to be managed by Charles Coster, a new Morgan partner who was to become the era’s greatest financial engineer, a veritable walking spreadsheet.

The Accidental Central Banker

Morgan’s role as de facto central banker for the United States was a consequence of the ignorant destruction wreaked by Andrew Jackson on the superb financial infrastructure bequeathed by Alexander Hamilton. Civil War– era reforms patched over some of Jackson’s depredations, but as America’s economic power mounted, the lack of a central banking authority became both glaring and dangerous.

The Great Merger Movement

The typical company swept up in the merger mania, according to a profile developed by the historian Naomi Lamoreaux, was a medium-sized business in an industry with modestly high fixed costs and rapid growth. Papermaking is a good example. The explosion of print media in the 1880s and 1890s, and modern Fourdrinier papermaking machines, created mouthwatering opportunities for ambitious entrepreneurs. But the machines were almost too affordable—right in the gray area where a midsize business could buy one, but then couldn’t afford to let it sit idle.

The result was a deadly cycle of temporary scarcities, waves of new competitors, price wars and competitive shakeouts, followed by another round of scarcity, and another wave of entrants. Wire and nail makers and makers of tin plate (coated sheet steel for tin cans and roofing material) showed an almost identical pattern.

America Rules

What Happened to England?

A near-obsessive search for the causes of the relative British decline spurred a century’s worth of economic history on both sides of the Atlantic that offers a superb lens for tracing the sources of American advantage.

The divergent paths followed by the American and British steel industries have been perhaps the most intensively researched and are a rich source of insights.

Loss of leadership in steel was especially painful for Britons. Steel was the foundation industry for the late-Victorian period, much as information technology is today.

The cost advantage once enjoyed by the British industry from its conveniently located ore and coal supplies gradually disappeared as Americans mechanized ore mining and transport through the 1890s.

American product standardization facilitated very large production runs, while British manufacturers were plagued by a multiplicity of product designs. Some of the British diversity stemmed from perverse pride in local idiosyncrasy, but it was also an inevitable consequence of serving a very diverse export market.

But why did Great Britain lose its leadership?

Britain, first of all, suffered the disadvantages that accrue to any path-breaker. By the time American and German competitors appeared on the scene, the structure of the British industry already had a long-settled character.

In contrast to the big American plants, British steel-making stayed resolutely craft-oriented. Jeans noted that three-quarters of British steelworkers were in skilled crafts categories, few of which still existed at American plants. Mechanization, moreover, was hindered by the smaller scale of British plants.

Mechanical furnace chargers and automated rolling mills were too expensive for any but the largest works. The enormous size of the American home market readily conduced to very large plants that could fully exploit scale economies; German plants were similarly of very large scale. The slowdown in British steel itself created problems.

Finally, a long finger of suspicion points at both British workmen and British managers. Most fair-minded observers conceded that American and German workers and bosses were better educated and more open to scientific advances than their British counterparts. Worker recalcitrance and union resistance were a major obstacle to mechanization at all British plants.

Finally, there is another factor in the relative British decline: the very aggressive use of the protective tariff, especially in steel, and especially by America and Germany, against a British nation that, despite some wavering, steadfastly refused to deviate from its free-trade principles.

The Carnegie Effect

It was the high cost of British steel, not the tariff, that set the price ceiling for the Americans. A substantial share of the credit for keeping the tariff burden so low must go to Andrew Carnegie. The deadweight costs of a protected cartel are some of the most destructive consequences of a high-tariff regime. But Carnegie never behaved like a rational cartelizer. Although he consistently earned the highest profits in the industry, he paid the smallest dividends, choosing instead to plow earnings back into better plants, more mechanization, and larger output. Falling prices were just opportunities to take share

American steel producers enjoyed great natural advantages in their vast coal reserves and the nearly infinite, low-cost Great Lakes ore ranges. But it required huge investments to bring that potential to fruition. Cost-effective use of Mesabi ore came only with the advent of large-scale surface mining machines, mechanized loading and unloading docks, massive ore boats, and purpose-built railroads, like Carnegie’s Pittsburgh and Bessemer line.

What Was Special about America?

Lincoln’s claim that the average man “labors for wages a while, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land, for himself . . . and at length hires another new beginner to help him,” was sufficiently true that it became the standard to judge oneself by.

A land of abundance was the perfect incubator for a machine-based business culture—with free resources, any method of accelerating output built wealth.

Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Jay Gould, the archetypes for the megatycoons that dominated the second half of the century, all arrived just at the cusp of the fateful post–Civil War transition from artisanal to big-business forms. All three came from modest circumstances, and while they were all men of great intelligence and lightning commercial reflexes, they separated themselves by the boundlessness of their ambition and their instincts for disruption.

The Wrong Lessons

But even if Taylor’s claims could be taken at face value, their essential triviality is astonishing.

There is a place in industry for engineered manual operations. But when presented with a problem like loading pig iron, an Alexander Holley or a Henry Ford would first ask, why on earth are you doing it by hand?

Taylor and the Intellectuals

The curt summary by the historian Phillip Scranton—that Taylor was “a batch and specialty shops veteran obsessed with eradicating variation and uncertainty”—has it exactly right.

It is not true that Henry Ford’s Model T factory was just a special case of Taylorism, as Alfred Chandler would have it, or Taylor himself claimed. Taylor’s machine shop work was aimed at increasing the production of skilled machinists making variable goods with general-purpose machines. The Ford factory, by contrast, was the apotheosis of the Armory tradition of making interchangeable parts with single purpose machines operated by unskilled labour. Instead of devising standardized instructions for machinists, as Taylor did, Ford eliminated machinists in favour of machine tenders.

The only overlap between Taylorism and a Ford factory is that the Ford engineers conducted what they later called time and motion studies to work out the speed of the line and the best layout for assembly materials.

…And There Were Consequences

The American “pursuit of quantity and speed,” Ohno suggested, produced only “unnecessary losses.” Vertical integration was usually wasteful; it was more efficient to develop stable supply relationships with specialist contractors (in contrast to the adversarial American contracting culture).