Summary

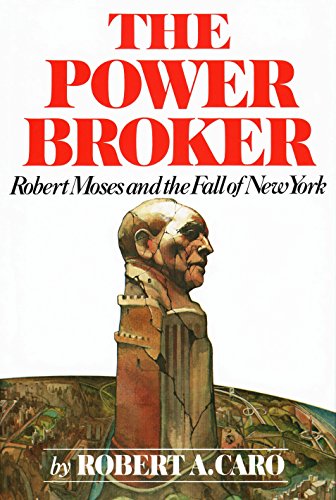

This massive 1200-page biography has won every award imaginable and for good reason. Robert Moses shaped the physical nature of New York for 40+ years and his influence is felt around the world. This book covers his ascent, control and loss of power. Many things to learn from his life. Extremely well-researched and well-written. The only reason I don’t rank it higher is its length.

Key Takeaways

To be added on a reread. See notes below.

What I got out of it

To be added on a reread. See notes below.

Table of Contents

Summary Notes

Introduction – Wait Until The Evening

An understanding that ideas-dreams-were useless without power to transform them into reality. Moses spent the rest of his life amassing power, bringing to the task imagination, iron will and determination.

The greatest secret was how to remove people from the expressways’ paths-and Robert Moses taught them his method of dealing with people. This method became one of the trademarks of the building of America’s urban highways, a Moses trademark impressed on all urban America.

The wealth of the empire enabled Moses to keep many city officials in fear. With it, he hired skilled investigators he called “bloodhounds” who were kept busy filling dossiers. Every city official knew about those dossiers, and they knew what use Moses was capable of making of them-since the empire’s wealth allowed him to create an awesomely efficient public relations machinery.

For forty years, in every fight, Robert Moses could count on having on his side the weight of public opinion.

Beyond graft and patronage, moreover, Moses also displayed a genius for using the wealth of his public authorities to unite behind his aims banks, labor unions, contractors, bond underwriters, insurance firms, the great retail stores, real estate manipulators-all the forces which enjoy immense behind-the-scenes political influence in New York.

Corruption before Moses had been unorganized, based on a multitude of selfish, private ends. Moses’ genius for organizing it and focusing it at a central source gave it a new force, a force so powerful that it bent the entire city government off the democratic bias. He had used the power of money to undermine the democratic processes of the largest city in the world, to plan and build its parks, bridges, highways and housing projects on the basis of his whim alone.

I – The Idealist

1. Line of Succession

For while the motives which impelled the rich Jews to help the poor Jews were certainly in part manifestations of Zedakah, the religious principle of charity, historians have also found other motives. They have found that many German Jews-solid, respectable, Americanized-were embarrassed by the gruff, uncouth, shaggy-bearded, conspicuously un-Americanized new-comers.

For this reason, the early settlement houses, while work-ing tirelessly to give the newcomers a better life, to provide free lodging, meals and medical care, also emphasized lectures on manners, morals and the dan-gers of socialism.

Some of Bella’s proposals were based on generalized theories. You should always buy the best, she would say. Having the best equipment made people respect it-and take care of it.

She was convinced also of the importance of symbols. They were needed, she said, to “give the children a sense of identity,” by which she meant a sense that they were part of Madison House.

Once Bella got involved in a project, no task was too small for her.

After he moved to New York, Emanuel Moses did a lot of reading. “Read-ing,” he would often say, “is the solace of old age.”

2. Robert Moses at Yale

It was the reading and writing he did behind the door closed against his classmates’ shouts that first made them take an interest in him.

There was on the campuses of that era a respect for scholarliness and brilliance, and Bob Moses’ classmates slowly began to realize the extent to which he possessed these qualities.

Not only had Bob Moses read most of Pater; he believed in what he had read. He loved learning genuinely and for its own sake. If he was competitive in swimming, he wasn’t in classroom work. He wasn’t uninterested in marks, but he wasn’t especially concerned about them either. He spent night after night behind a closed door reading, but his friends began to realize that the reading was not for grades; some-times they would look at the stack of books on his desk and not one of them had anything to do with the courses he was taking; they were there because they interested him. And their subjects covered a wide spectrum of knowl-edge; if Moses seemed particularly fascinated by literature and history, he was also reading everything he could find on the history of art.

The friends Bob Moses selected were of a specific type: cultured, artistic, interested in the things he was interested in

But what was, perhaps, significant about Bob Moses and the Class History was not that his name appeared in it infrequently but that it appeared in it at all. His achievements at Yale might be dim beside those of the prep-school Episcopalian leaders of the secret societies, but they were bright indeed for a Jew. If in his first two years at Yale Bob Moses had been a lonely nobody, in his last two years he had become considerably more than that.

And the way in which he had become more was, in the light of his later career, even more significant. He became a campus figure partly, of course, because of the brilliance and idealism that were part of his inher-itance. He displayed also, in his refusal to knuckle under to Walter Camp, his inherited stubbornness-and a considerable amount of real moral courage. But, in the light of his later career, what is most interesting is that when he realized that, because of the handicap of his religion, his brilliance and idealism would not take him to the top in the world of Yale, he made, within Yale, a world of his own, and a world, moreover, in which, in col-legiate terms, he had power and influence.

The men in the coterie admired Bob Moses. The men he chose to be his friends were happy to be chosen.

3. Home Away from Home

Brilliance, idealism and arrogance.

Oxford, using the brilliance as catalyst, was to refine the other two ingredients in the strain.

Oxford’s exemption of students from all marks and tests except for a single, all-inclusive examination given after two years appealed to the student who even at Yale had refused to be bound by the confines of his courses.

“The Oxford education … confers on the average undergraduate independ-ence of mind,” he wrote in the Alumni Weekly.

“Open competition” may be what the young author said he wanted-but the openness was to certain individuals only. “Merit” may be the deter-minant he said he desired, but it was not merit based on a man’s handling of his job. The competition Moses wanted was a competition open only to a highly educated upper class. The merit he was talking about was merit not in public service but in the education given exclusively to members of that class.

What Moses admired in the British civil service was that it had two separate and distinct classes: a very small administrative and policy-making “upper division” reserved for “university men,” and a much larger “lower division” consisting of “clerks of ordinary education” selected through examinations on the high-school level who “do the lower and more mechanical work.” The class differentiation that Moses admired was a rigid one. Carefully placed technical hurdles made it difficult, almost impossible, for a young man, even one of dedication, industry, ambition and talent, to rise out of the lower division.

II – The Reformer

4. Burning

As the time was right for Bob Moses, so, seemingly, was the place. If there was an epicenter of the idealism that was rolling across America, it was the ninth floor of 261 Broadway. The impulse to do good may have been rampant beneath the domes of statehouses and the national capitol, but it reached its zenith in city halls. Perhaps this was because in cities corruption was more visible than in federal politics, issues more succinctly dramatized.

Or perhaps it was because the reforming impulse thrived on problems, and it was in the cities, swelling with the immigrant tide, faced with problems of housing, schooling, policing, fire protection, traffic regulation and sewage disposal on a new scale, that America’s problems were beginning to ;loom largest.

The emphasis of natural science on empiricism, on firsthand observation, on the obtaining of facts, led them to conclude that it was vain to talk about changing the philosophy of government before learning the facts of government, and they said therefore that the first step toward reform should be analysis of govern-ment operations. From scientific management-the age was marveling at the assembly-line techniques introduced by Henry Ford-they concluded that after government operations had been analyzed, the next step should be not a change in philosophy but an improvement in such operations to make them “efficient” and “economic,” to insure that the city would get far more for each dollar spent than in the past, and would therefore be financially more able to do what the voters desired.

Said Bruere: “There was the constant futile search for the great administrator, great by instinct and personality. He wasn’t found because he doesn’t exist.

A great administrator needs the tools and techniques of sound administra-tion.” The search, he said, “should not be so much for good men as for these good tools and techniques; the idea should be not so much to jail the grafters as to install [in government] business systems which will make grafting dif-ficult.” Before government could become humanitarian, he said, it must be-come businesslike.

Most of them found it.” The young men developed techniques that were to reform every aspect of municipal government and create “a new literature on the science of public administration.” They devised the first budget used by any municipal govern-mental unit

They invented line-by-line itemization to eliminate lump-sum budget requests, and organization charts similar to those coming into use in business to make responsibility easier for voters to pinpoint.

At first, he was very popular with the other students. He was pleasant and friendly and had a gift for putting people at ease. Many of the students admired Moses.

The young idealists admired Moses most for his education. It wasn’t just that he had been to Yale; the world’s principal centers of education for public service were Oxford and the University of Berlin, and Moses had studied at both.

The students began to notice another quality in Moses, a quality which became more apparent almost day by day.

Blazing behind the big gray eyes, they now saw, was a furious impatience.

Within months after entering the Training School, Moses made clear that he felt he had learned all it had to offer.

He began to press for admission to the Bureau itself, making clear that, because he had an allowance from his mother, he would require no salary; within a year, on that financial basis, he was admitted; his student days were over.

No sooner was he in the Bureau than he began to make cutting comments about its procedures: the voluminous filing and cross-filing of all information was a waste of time, he said; the weekly staff luncheons were a waste of time; the Bureau’s constant emphasis on procedure was a waste of time. The Bureau wasn’t “getting enough done,”

No matter how many “technicalities” it dispensed with, simply because the Bureau was merely an agency that investigated and advised government. The way to get things done, Moses was making clear, was to be in government.

But if there was ambition, that was only a part of what was driving Bob Moses. And the whisperers never saw the other part. For they never saw what Moses did in the late afternoons after he grabbed the taxicabs.

He would be looking down. Below him, along the edge of the river, was a wasteland, a wasteland six miles long, stretching from where he stood all the way north to 181st Street. The wasteland was named Riverside Park, but the “park” was nothing but a vast low-lying mass of dirt and mud.

“Isn’t this a temptation to you? Couldn’t this waterfront be the most beautiful thing in the world?” As the woman looked at him in astonishment, words began to pour out of Bob Moses and she realized that “he had it all figured out.

Bob Moses had the exact location of tennis courts and boat basins quite definitely in mind; the young Bureau staffer beside her was talking about a public improvement on a scale almost without precedent in turn-of-the-century urban America, an improvement that would solve a problem that had baffled successive city administrations for years. And “he had it all figured out.”

The ideas were good; what was needed now was to put them into practice.

Bob Moses hurled all his energy and all his bril-liance, all his zeal for reform, all the long-pent-up enthusiasm and fire of the boundless idealism of his youth.

5. Age of Optimism

The only source of jobs on the scale required was the city itself. So the jobs Tammany had to control in order to control the city were the city’s jobs-positions as policemen, firemen, sanita-tion workers, court clerks, process servers, building inspectors, secretaries, clerks. There were, in 1914, 50,000 city employees and this meant 50,000 men and women who owed their pay checks-and whose families owed the food and shelter those pay checks bought-not to merit but to the ward boss. Patronage was the coinage of power in New York City.

Moses said that the first step had to be a reform of the city’s efficiency-rating system, the system of ratings given by supervisors to their subordinates to help determine whether to promote a civil service employee or give him a pay raise; under the present method, ratings didn’t give the Civil Service Commission enough information for a sound judgment.

Making an evaluation system precise was perhaps the most difficult job in civil service, Moses explained; each job had to be broken down into component parts, so that each part could be graded, and in totaling the grades each part had to be given a mathematical weight corresponding to-its importance in the job as a whole.

The Bureau assigned ten men to Moses as assistants. The idea of working under him didn’t appeal to the older men, but the younger ones, who hadn’t known him before, liked him. “He worked all of us hard,” one of them recalls. “But he worked himself harder. He was at the Bureau when you got in in the morning, and he was still there when you left at night. He’d lose his temper, but it was silly to argue with him anyway, be-cause you knew darn well that he had looked the point up before he talked to you and knew it better than you did.”

Moses’ proposal was a codification of idealism.

There was to be only one standard for promotion in public life: “open competition,” how hard and well a man worked and how he performed on examinations. Examination results would be posted in public, and report cards would be open to public inspection so that every city employee would know the basis whereon he and his competitors were judged. Seniority would become unimportant; not experience but ability would be crucial.

“We talked about everything under the sun,” Gove recalls-art, philosophy, history. The one subject not mentioned was one other young men might have dwelt on: making money. “He just wasn’t interested in that,” Gove says. The subject that dominated the talk was government and par-ticularly the government of New York City. “He was all caught up in his work,” Gove says.

Moses was sure the work was going to pay off.

Moses wasn’t at Oxford any more. The only effect of his courage was to make things easier for his enemies. Civil service reorganization was a subject so complicated that it was difficult to interest even civil service workers in it. What was needed was a single, visible object on which the workers could focus their hatred. And now Moses had given them such an object-himself.

The outspokenness and the courage, along with the arrogance and the lecturing tone, had no effect other than to increase the opposition to his system, to rouse the fury of 50,000 voting men and women to fever pitch.

Moses argued against compromise. If the principle behind his system was right, he said, there should be no compromising with it. Making ex-ceptions, he said, would kill the whole plan.

In an attempt to help men who might try to reform civil service in other cities, Moses summed up in a speech to a political science convention “certain deductions” which he had made from his experiences. The main deduction was a simple one. “Executive support” was the essential you could not do without.

Intending to reform the city, he had worked hard and mastered with a supreme mastery reform’s techniques. Convinced he was right, he had refused to soil the white suit of idealism with compromise. He had really believed that if his system was right-scientific, logical, fair-and if it got a hearing, the system would be adopted. In free and open encounter would not Truth prevail? And he had gotten the hearing.

But Moses had failed in his calculations to give certain factors due weight. He had not sufficiently taken into account greed. He had not suffi-ciently taken into account self-interest. And, most of all, he had not sufficiently taken into account the need for power.

III – The Rise To Power

6. Curriculum Changes

Because the Governor stood at the head of the state and represented all of its people rather than just one assembly or senate district, the Governor must be held responsible if the state failed to move as the voters wanted it to move. But going hand and hand with responsibility, the Bureau said, must be power. If a man was to be held responsible for moving government, he must be given power to move it, “executive power commensurate with executive responsibility” in the Bureau’s slogan.

There was a bigger difference between working for the Bureau and working for Belle Moskowitz than sumptuousness of office arrangements. The Bureau made recommendations; Mrs. Moskowitz made laws. The Bureau got enthusiastic and excited; Mrs. Moskowitz got things done. And no sooner had her chief of staff begun work, two weeks before his thirtieth birthday, than she began to teach him how things got done.

“Moses was very theoretical, always wanting to do exactly what was right, trying to make things perfect, unwilling to compromise. She was more practical;

she wanted to do the same things as Moses, but she wanted to concentrate on what was possible and not jeopardize the attaining of those things by stirring up trouble in other areas.”

Moses was not only obeying Mrs. Moskowitz but also obviously studying the lessons that she was teaching, and studying them hard. His conversation began to include the phrases of practi-cal politics as well as those of scientific management textbooks. His analysis of a state job began to take into consideration not only whether the position was necessary for the betterment of mankind but also who had appointed the man who now held the position. He learned to weigh the governmental gains that might be achieved by the position’s elimination and by the use for worthier purposes of the salary allocated to it against the political losses the elimination might entail-how much it would antagonize the appointer and how great an obstacle such antagonism might be to Smith’s over-all program.

It was not just that he obeyed Mrs. Moskowitz and it was not just that he learned her way of thinking; rather it was that, after a while, he seemed almost eager to learn.

Working for Moses as one of the high points of their lives.

“‘Dedication’ has become sort of a phony word,” staffer John Gaus said shortly before he died in 1969, “but that’s what Moses had. People who are terrifically hard workers you have got to respect anyway, but it was more than just how hard he worked. He was a vibrant and driving person-you just knew that if you wanted to work for him, you had to be on your toes, but on the other hand that you would be treated with complete frankness, and you also knew that here was one person who was really thinking of the public interest above everything else. He talked to you hard and direct, but he made you feel that you were both on the same side, fighting for the same things. He made you want to work for him.”

7. Change in Major

On the desk he would earlier have piled the bills that had been introduced that day. AI Smith would begin reading them. Not only the bills which bore on a subject in which he was interested, and not only the bills which dealt with his Assembly District, and not only the bills which dealt with New York City. Sitting at the rickety desk in the furnished room, Smith read all the bills, even those which concerned the construction of a side road or a tiny dam in some remote upstate district.

And as he read them, he tried to understand them. Why had one legislator included in a bill a provision that the dam be built by the Conservation Department rather than by the Department of Public Works? What had been in the mind of another that led him to specify that the side road must be surfaced with a specific type of asphalt?

When he went back, he read harder. Since most of the bills amended or referred back to other bills passed years before-and not described in the new bills-he took to spending evenings in the Legislative Library reading those old bills. Since some of the most confusing wording was based on legal technicalities, Smith began to borrow lawbooks from law libraries and take them back to the furnished room with him. Sometimes, leafing through the thick volumes, he thought wryly that their very appearance would have in-timidated him a few years before. Tired of listening to speeches he couldn’t understand, he would pay clerks for transcripts and study the transcripts.

Near the end of the session, the annual appropriations measure, hundreds of pages long, containing tens of thousands of items, was published. No one, so far as anyone in Albany could remember, had ever read the entire appropri-ations bill. In 1906, AI Smith read it.

Foley would say, “He would never admit that he knew anything about a subject until he knew everything about it.”

Most legislators spent as little time as possible in Albany, coming to the capital only one or two days a week and spending the rest of their time attending to their outside business interests. Murphy saw to it that Smith was offered a well-paying position with a firm doing business with the city. Finances were still tight for Smith.

He could have used the money. But he turned the offer down. Instead, he spent most of every week-all of many weeks-in the capital. Not only did he attend every hearing held by every committee of which he was a member but, legislators began to notice, he would slip quietly into hearings held by committees of which he was not a member and sit in the back of the hearing rooms, following the testimony intently. At night, he would still party loudly and happily-and he would still slip away from most parties early.

The State of New York reaches out to them, “We recognize in you a resource of the State and we propose to take care of you, not as a matter of charity, but as a government and public duty.” What a different feeling that must put into the hearts of the mother and the children!

The man who had always talked-and who still talked-of most politicians with such scorn talked of Smith with respect and admiration and something that was close to reverence. Moses’ brother and friends saw nothing wrong with such a feeling. But they couldn’t help noticing that, in discussing Smith, Moses was talking less and less about the great issues of the time with which Smith had been involved and more and more about political maneuvers which the former Governor had de-scribed to him. “Why, when he got enthusiastic about something now, and started to really go on about it in that way he had, it was more than likely something that, when you thought about it later, was really nothing more or less than some cheap political trick,” one friend said.

Under Belle Moskowitz’s tutelage, Bob Moses had changed from an uncompromising idealist to a man willing to deal with practical considerations;

now the alteration had become more drastic. Under her tutelage, he had been learning the politicians’ way; now he almost seemed to have joined their ranks.

More, he was openly scornful of men who hadn’t, of men who still wor-ried about the Truth when what counted was votes. He was openly scornful of reformers whose first concern was accuracy, who were willing to devote their lives to fighting for principle and who wanted to make that fight without compromise or surrender of any part of the ideals with which they had started it.

Bob Moses was scornful, in short, of what he had been.

8. The Taste of Power

Watching Smith banter with reporters, seeing how much time he devoted to winning their friendship, Moses learned how important the press was in politics. Seeing that Smith used the banter to cover up the fact that he wasn’t telling the reporters anything he didn’t want them to know, Moses learned how the press could be used.

He could learn to keep things simple. The Governor wanted no tech-nicalities in his speeches: he himself, with the genius that made him the greatest campaigner of his time, reduced every argument to its most basic terms.

“Executive support,” he had learned, was the essential that one could not do without if one did not have power of one’s own. Now he had that support.

And he got a lot done.

Bill drafting was called by Albany insiders “the black art of politics.” An expert bill drafter had to know thousands of precedents so that he could cull out the one, embodying it in the bill he was working on, that would make the bill legal, or so that he could, by careful wording, avoid bringing the new act within the purview of an old one that might make it illegal. He had to know a myriad ways of conferring, or denying, power by written words. He had to know how to lull the opposition by concealing a bill’s real content.

For years, everyone had known the identity of the best bill drafter in Albany:

Alfred E. Smith. And Smith had never been shy about accepting that ac-colade. But now, when someone brought up the subject, Smith said, “The best bill drafter I know is Bob Moses.”

AI Smith was a man who believed in paying his debts. In 1923, he found for Moses a state sinecure with high pay and a low work load: the directorship of a board that would supervise the industries that, thanks to Moses, had been installed in state prisons.

Moses told Smith he didn’t want the job.

“What do you want, then?” Smith asked.

“Nothing,” Moses replied.

Over and over during 1923 and the beginning of 1924, as Smith watched Moses driving himself in his service, he asked Moses what he wanted. Over and over again, Moses said, “Nothing.” And then, one day, there was something. The something was parks.

9. A Dream

And it was neither the baymen nor the farmers who most firmly barred Long Island to those who hungered for it. The huddled masses of New York City had a far more powerful enemy. It was wealth-vast, entrenched, im-pregnable wealth-and the power that went with it. For it was to Long Island that the robber barons of America had retired to enjoy their plunder.

Their creed was summed up in two quotes:

Commodore Vanderbilt’s “Law? What do I care for law? Hain’t I got the power?” and J. P. Morgan’s “I owe the public nothing.”

Horace 0. Havemeyer, the “Sultan of Sugar,”

Given the need, therefore, and the possibility that Long Island could meet it, the thoughts of reformers interested in parks had for years turned first to the Island. Here, they all saw, was the land of the greatest opportunity.

But they also saw, even the most unrealistic of them, that the amount of power with which they had to contend on Long Island was such that efforts to create parks there seemed, even to themselves, foredoomed.

Behind him, not a quarter mile from the road but unknown to all but one in a thousand of the drivers on it-and closed to even that one-was land, a vastness of land, overflowing with the fruits they sought. Land that didn’t have to be purchased. Land that didn’t have to be condemned.

Land that was owned not by the governments of Long Island, which viewed the masses of New York City as foreigners, but by the government of New York City. Land that could be opened to the city’s people merely by turning a key.

The mind leaped on. It took as its compass not an island but a state.

The state’s other large cities-Albany, Buffalo, Rochester, Schenectady, Syracuse, Troy, Utica-were growing, not as fast as New York but fast enough. So was their need for state parks.

But the State Legislature, considering parks a luxury outside city limits, refused to give them any.

Part of the difficulty, Moses had learned while running the Reconstruc-tion Commission, went back to the old question of organization. Fearing-knowing-that the state would let them run down, the parks’ donors had turned their administration over to men or societies dedicated to the preservation of historic or scenic attractions.

Having no authority over private individuals or organizations, the Legislature was reluctant to give them money. And since no central body of any type unified their activities, they presented to the Legislature the spectacle of separate agencies competing with each other for funds.

This lack of unified administration also meant that a considerable poten-tial source of power for parks was dissipated.

A State Park Plan for New York, which he wrote himself and issued in the name of the New York State Association.

The report was a seminal document in the history of parks in America.

Its scope was in itself revolutionary: New York’s park needs, it said, were so great that they could not be met by ordinary legislative appropriations;

a bond issue would be required-and the amount of the issue should be $15,ooo,ooo. But it was not the scope that startled most; New York and other states had floated bond issues for parks before, even if none of the issues had been nearly so large as that Moses proposed. Rather, it was the philosophy. The expenditure of proceeds from previous bond issues had been restricted to land acquisition and in the word “acquisition” was em-bodied the philosophy that had always in the past governed parks in America, the belief that parks were only land and the trees and grass and brooks on the land, that their sole purpose was to serve as “breathing spaces” for the city masses and to enable them to relax and meditate among beautiful sur-roundings, to commune with nature, and that they should therefore be kept in their natural state. If the city masses no longer were content with com-muning, if they wanted space not only to meditate but to swing-to swing baseball bats, tennis rackets, golf clubs and the implements of the other sports that their new leisure time had enabled them to learn-this was a desire that had not yet been translated into governmental action in the United States.

AI Smith, shrewd politician, had risen to the Governorship on great issues, and he was not slow to recognize a new one when it came along. An Albany reporter watched the awareness grow on the Governor and his circle.

“You could see them beginning to realize that doing what Moses wanted would be politically advantageous,” he recalls. “One of them told me that supporting parks meant that the Governor would be helping the lower- and middle-class people, and thereby winning their support, and that the intellec-tuals would be for him because they saw parks as part of the new pattern of social progress. So you’d have all three groups supporting you. And besides, ‘parks’ was a word like ‘motherhood.’ It was just something nobody could be against.”

10. The Best Bill Drafter in Albany

It was not, moreover, the violation of stated principles for the purpose of cementing himself in office that most clearly revealed the change in Moses.

Rather, it was the method by which he insured that, once in office, he would have specific powers sufficient for his purpose. For the method was that of concealment and deviousness.

Once, no reformer, no idealist, had believed more sincerely than he in free and open discussion. No reformer, no idealist, had argued more vigor-ously that legislative bills should be fully debated, and that the debates should be published so that the citizenry could be informed on the issues.

But free and open debate had not made his dreams come true. Instead, politicians had crushed them. And now he was going to make sure that, with the exception of AI Smith and Belle Moskowitz, no one-not citizenry, not press, not Legislature-was going to know what was in the bills dealing with parks that the Legislature was going to pass. The best bill drafter in Albany set to work.

IV – The Use of Power

11. The Majesty of the Law

By the end of the summer of 1924, he seemed well on his way to establishing a state park system on Long Island on the basis of his charm alone.

But the charm could vanish swiftly. He joked and laughed with the farmers, but when one made clear that he would not sell his land, Moses could change in an instant to quite a different approach.

‘You know, Mr. Rasweiler, the state is all-supreme when it comes to a condemnation proceeding. If we want your land, we can take it.’

“Father wanted to make an agreement with him-he didn’t want to have to go to the lawyers-but Moses wanted to take twenty acres from us. The whole farm was only eighty, eighty-five acres. The twenty acres was the choice of the whole farm. It had been woodland; we had worked hard to get it cleared off. We had just gotten it cleared, and it was just about ready to begin making money for us. It was right in the middle of the farm; if he took it, all our rows would be cut in half-how could you plow? And he was offering us $1 ,200-the same price he was offering for bad land on the edges of other farms. That wasn’t fair. But when we tried to explain that to him, he wouldn’t even listen to us. Father asked him to go on the north boundary line instead. Father said if he’d take it from the boundary and not from the middle, he’d give it to the state for nothing. But Moses said no.

His whole attitude was: ‘This is where we’re going, and that’s it.’”

Section fifty-nine of the Conservation Law gave the commission the power to appropriate land, the attorneys said, but section fifty-nine also said that the power could be used only after negotiations with property owners had failed and no price could be agreed upon. Moses had never negotiated; he had never bothered to mention a price to any representative of Pauchogue; he had never even spoken to any representative after Pauchogue had purchased the Taylor Estate. Moreover, the State Constitution forbade any state agency to buy, condemn or appropriate land unless it had enough money on hand to pay for it.

The fight for the Taylor Estate was not. It would be waged without quarter in both regular and special sessions of the New York State Legislature, and in twenty-five separate appellate court proceed-ings. It would fill the front pages of newspapers across the state for two years, delay for almost that long all expenditures for any of the parks of which Robert Moses had dreamed, and bring to the brink of ruin not only those dreams but Moses’ personal reputation and career. But before it was over, Moses would be hauled back from the brink by AI Smith, with a helping tug from Belle Moskowitz, and his reputation, seemingly certain to be tarnished by his actions, would be burnished instead so that he gleamed in the public consciousness with the aura he would bear for the next thirty years: the aura of a fearless, fiercely independent public servant who loved parks above all else and was willing to fight for parks against politicians, bureaucrats and the hated forces of wealth and influence.

If Moses could do this to us, Macy said, he could do it to anyone. “No one’s home is safe.” The principles, he said, were too important to be surrendered without a fight.

While Macy had won the first round in a court of law, Moses had won the first round in the court of public opinion.

In the Legislature and the courts, then, the issue appeared in February 1925 all but settled: To realize a dream of unprecedented scope, Robert Moses, by use of the law, had armed himself with unprecedented powers-and then, finding that these powers were still inadequate, he had deliberately gone beyond them, beyond the law. “Entry and appropriation” was, even as defined in law, of questionable constitutionality in its negation of the individual’s rights when his property was coveted by the state. And Moses had gone beyond the definition to use the power of the state with even less restraint than the law allowed. But both courts and Legislature understood the situation; before both courts and Legislature, Moses stood stripped of all defenses and, it seemed in February 1925, both courts and Legislature would now step in and rectify the situation, the courts by affording redress to the individuals injured by his actions, the Legislature by insuring that he never again had the opportunity similarly to injure any other individual

But the ultimate court in which the fate of Moses and his dream was to be resolved would be the court of public op1mon. And in this court, Robert Moses had close to hand three formidable weapons.

One was the fact that, like motherhood, parks symbolized something good, and therefore anyone who fought for parks fought under the shield of the presumption that he was fighting for the right-and anyone who opposed him, for the wrong.

The second was the fact that it was possible to paint the issue, as Moses had already done, not only as park supporters vs. park deniers, but also as wealth vs. lack of wealth, privilege vs. impotence, influence vs.

helplessness, “rich golfers” vs. the sweating masses of the cities.

The third was the ultimate political weapon: Alfred Emanuel Smith.

All through April and May, Moses, anxious, was nudging the Governor to call the special session. So, for less personal reasons, were Smith’s other advisers. Since he had a great issue, they said, wouldn’t it be best to press it while it was still fresh in the public’s mind?

Wait, Smith said. He had thought of something his advisers hadn’t.

New York City wasn’t hot in April. It wasn’t hot in May.

They hadn’t yet reached the point at which all that mattered was that someone was trying to provide them with a place to swim-and someone else was standing in his way.

On June 10, Smith announced the special summer session-in a speech that was the first ever carried on a statewide radio hookup.

Smith said, “there is a greater question here than Park Councils, Attorney Generals or Land Boards. There is a question of what will ulti-mately become of the $I s,ooo,ooo authorized by the people. Will it buy choice park spots and locate parkways where there is fine air and scenic beauty, or will money, power and influence compel the state to buy for the people that which nobody else wants? The people are either going to get these parks and parkways through the properly organized commissions …

or this program will be given into the hands of the very men who now desire to weaken it in the interests of the few … “

“The cure for the evils of democracy is more democracy. Let us battle it out right in the shadow of the capitol itself and let us have a decision, and let us not permit the impression to go abroad that wealth and the power that wealth can command can palsy the arm of the state.”

“Sacred constitutional property rights” and the price of office furnishings weren’t the issue to the steaming millions of New York City-or of the state’s other cities. Twice more before the session Smith took to the air to speak, twice more he pounded on the theme of the few against the many, of wealth, privilege and influence against the masses, of parks against the millionaires’ golf clubs.

And the press didn’t help the Republicans.

It was not just a case of inequality in space and play. The Times’s articles repeated, day after day, as if they were uncontested facts, the key contentions made by Moses and Smith.

The key contentions of Moses’ opponents were almost totally ignored.

Whatever the reason, the daily press coverage of the park fight made Smith and Moses look very good-and the Republican legislators look very bad.

At the end of 1925, Robert Moses might well have thought he had lost his entire Long Island dream.

The only concrete result of all the talk about parkways on Long Island had been an increase in the rate at which real estate promoters were littering the Island with their rows of houses.

At the end of 1925, there seemed little possibility that they would come into existence at any time in the foreseeable future. If one looked ahead a decade, even a generation, it seemed unlikely that any substantial part of the dream would be reality.

Within three years, almost all of it would be reality.

12. Robert Moses and the Creature of the Machine

To take advantage of the financial opportunities provided by a parkway, a politician had to have foreknowledge.

And politicians had a weapon they could use in obtaining such advance informa-tion; if they did not get it, they would not approve the building of the high-way.

Whether Dunne’s decision would have remained the binding legal word in the case if both sides had continued the legal battle on equal terms, if both sides had continued to make use of all their remedies at law-if the Pauch-ogue Corporation had been able to press through higher courts its appeals as the Long Island Park Commission had been able to press its appeals-is impossible to determine. For both sides weren’t equal.

Lawsuits take money. The state’s supply of this commodity is com-paratively bottomless. The private citizen’s is not. And now W. Kingsland Macy was running out of money.

Robert Moses had also learned from the Taylor Estate fight, his first use of power, lessons that would govern his behavior for the rest of his life.

One was that the simplest method of accomplishing his aims was to use the power he possessed in all its mani-festations, even those that as recently as a year previously he had shrunk from using.

What did he care if Doughty’s friends made money from his dreams?

If they did, he had learned, the dream would become reality. If they did not, he had learned, it wouldn’t. And the dream was the important thing; the dream was what mattered.

Another lesson Moses learned was that, in the eyes of the public, the end, if not justifying the means, at least made them unimportant.

The value of parks as an issue was another lesson. As long as you were fighting for parks, you could hardly help being a hero.

As long as you’re fighting for parks, you can be sure of having public opinion on your side. And as long as you have public opinion on your side, you’re safe. “As long as you’re on the side of parks, you’re on the side of the angels. You can’t lose.”

Once you did something physically, it was very hard for even a judge to undo it. If judges, who had to submit themselves to the decision of the electorate only infrequently, were thus hogtied by the physical beginning of a project, how much more so would be public officials who had to stand for re-election year by year?

“Once you sink that first stake,” he would often say, “they’ll never make you pull it up.”

These lessons had other implications. If ends justified means, and if the important thing in building a project was to get it started, then any means that got it started were justified. Furnishing misleading information about it was justified; so was underestimating its costs.

Misleading and underestimating, in fact, might be the only way to get a project started.

And if they said you had misled them, well, they were not supposed to be misled. If they had been misled, that would mean that they hadn’t investigated the projects thoroughly, and had there-fore been derelict in their own duty. The possibilities for a polite but effec-tive form of political blackmail were endless.

If there was one law for the poor, who have neither money nor influence, and another law for the rich, who have both, there is still a third law for the public official with real power, who has more of both.

There was one more lesson.

Would dreams–dreams of real size and significance and scope-the accomplishment his mother had taught him was so important, ever be realized by the methods of the men in whose ranks he had once marched, the reformers and idealists? He asked the question of himself and he answered it himself. No.

13. Driving

Insisting that the engineers in charge of a project prepare a schedule showing the date on which each of its phases would be completed, Moses would move up the deadlines-by days, by weeks, some-times by months-until the engineers felt it was absolutely impossible to meet them. And then he insisted that they be met.

The men who stayed didn’t resent Moses’ methods. “If he drove other men hard,” says Junkamen, “he drove himself harder.”

There were other reasons, too, why the men who stayed didn’t resent the driving.

“It was exciting working for Moses,” one of the commission staffers recalls. “He made you feel you were a part of something big. It was almost like a war. It was you fighting for the people against those rich estate owners and those reactionary legislators. And it was exciting just being around him.

He was dynamic, a big guy with a booming laugh. He dominated that scene in the mansion. He would sit there with people running back and forth around him and he would be banging his hand down on that big table and giving orders-and when he gave orders, things happened!

And, men recalled, incongruous as it might seem to use the word “fun” in connection with unremitting work, it was, nevertheless, fun to work for Bob Moses.

The joking, the engineer says, went both ways. “You weren’t afraid to kid him.” He turned the commission staff into a big family. If he couldn’t get home to his wife and children as much as he would have liked, he brought them to his work.

“Bob used to say that the only decisions he made that were mistakes were the decisions he had neglected to talk over with Mary first.”

He and Mary organized outings and insisted that Howland, Latham, Shapiro, McNulty and Junkamen-and Tom McWhinney, with whom Moses was getting along famously-bring their wives and children along. The outings were very informal-fishing trips on the commission motor launch Apache or clambakes-and they were fun.

Of all the reasons why Moses’ men didn’t resent his driving, the one most frequently mentioned in their reminiscences is that he brought out the best in them.

“Mr. Moses was no lawyer, but he had a great knowledge and grasp of the law,” Junkamen would say. “He was not an engineer, but he had a great knowledge of engineering. He knew politics, he knew statesmanship-he was an altogether brilliant man. If you were working with him, you just had to learn from him-if only through osmosis.”

The peculiarities of man seemed sometimes to join with those of nature to thw’art Moses. But he would not be thwarted.

Always, day after day, summer and winter, Moses was out on the job, encouraging the men in the field. “People will work harder for you if they have a good time,” he told the Morses, and he urged the laborers working on Jones Beach to go swimming during their lunch hour. Organizing softball games on the beach, he umpired them himself. Joking with the men, he made fun about his hat. And he told them what a great project they were building. “He had a gift for leading men,” Shapiro recalls. “Those men idolized him. You’d see him walk up to a pickax gang that was tired and talk to them awhile and when he walked away, you could see those pickaxes swing faster.”

New Yorkers knew who was primarily responsible for the boon they had been given. It would have been difficult for them not to know. For the press was turning Robert Moses into a hero.

The lionization was on a scale as vast as the achievement. The Twenties was an age for heroes, of course, and if 1927 was Lindbergh’s year in the New York press, 1928 was Moses’.

And the praise, on front pages and editorial pages alike, continued day after day. If readers were reminded once during 1928 that Moses was serving the state without pay, they were reminded a hundred times.

Moses’ lionization in the press had a practical benefit. It insured that he would be allowed to finish the job he had started. No one would dare stop it now.

The Long Island dream was safe.

But these newspapers had little interest in the Long Island parks, and New York City newspapers had little interest in the upstate parks. So no newspaper, no matter how enthusiastic it was over what editorial writers called “Robert Moses’ great park program,” comprehended the full extent of the program’s magnitude–or the full extent of its greatness.

14. Changing

For once Bob Moses came into possession of power, it began to perform its harsh alchemy on his character, altering its contours, eating away at some traits, allowing others to enlarge.

Now that he had power, he was going to see that he got it.

He had never wanted to listen to people who disagreed with him. Now, in the main, he didn’t have to.

Some of Moses’ fights with the elderly park philanthropists could be viewed as conflicts of philosophy-as his determination not to allow his dreams to be thwarted by other men’s smaller-scale vision-although the closer one examines their details, the more it appears that the crucial conflict in each was between his demand for speed and their feeling that since once nature was altered by man, it could never be restored· to its original condition, any changes in the magnificent gorges and mountains which had been entrusted to them must be considered with painstaking care and designed to blend in with the existing topography

On other battles between Moses and the old park men, however, it is more difficult to place any philosophical interpretation. The nature of these fights hints that power was now, for the first time in his life, becoming an end in itself, that he was beginning to crave it now not only for the sake of dreams but for its own sake, that although, through his bill drafting, he had given himself much of the power in the field of parks, he was no longer satisfied with much of the power, that he now wanted all the power in the field.

If he could not oust them quickly, his actions seemed to indicate, he would wear them down.

In politics, power vacuums are always filled. And the power vacuum in parks was filled by Robert Moses.

Smith was not only a politician; he was a Tammany politician. In the simple Tammany code, the first commandment was Loyalty. Smith’s loyalty to his appointees was legendary. Once he gave a man a job, he was fond of saying, he never interfered with him unless he proved himself incapable of handling it.

Smith was well aware, as a politician, that every public improvement caused outcries.

15. Curator of Cauliflowers

Robert Moses himself was conspicuously uninterested in social welfare reforms. But these reforms would have been impossible of attainment without the executive budget and departmental consolidation and reorganization.

Even more impossible of attainment would have been another Smith achievement: while expanding manyfold the state’s role in helping its people meet their needs, he succeeded, over the course of his four terms, in sub-stantially cutting state taxes. Walter Lippmann called the reorganization of New York’s administrative machinery “one of the greatest achievements in modern American politics.” Robert F. Wagner, Sr., asked to name Smith’s most important achievement, said flatly: “The reorganization.” And many other states modeled their reorganizations directly on New York’s. Says Leslie Lipson, author of The American Governor from Figurehead to Leader, the definitive study of the development of state government in America, “New York is the great classic of the reorganization movement.” In that classic, Robert Moses played the leading role.

When the Governor had said he would put Moses in charge of the Cabinet, he meant really in charge. At his direction, Moses assumed responsibility for spurring the heads of other departments into the gallop at which Smith wanted them to move.

Moses had always possessed tremendous energy and the ability to discipline it. Now he disciplined it as never before, concentrated it, focused it on his work with a ferocious single-mindedness.

Sloughing off distractions, he set his life into a hard mold. Shunning evening social life, especially the ceremonial dinners that eat up so much of a public official’s time, he went to bed early (usually before eleven) and awoke early (he was always dressed, shaved and breakfasted when Arthur Howland arrived at 7: 30 to pick up the manila envelope full of memos).

The amenities of life dropped out of his. He and Mary had enjoyed playing bridge with friends; now they no longer played. Sundays with his family all but disappeared. He did not golf; he did not attend sporting events; he was not interested in the diversions called “hobbies” that other executives considered important because they considered it important that they relax; he was not interested in relaxing. Since he left to Mary the paying of bills and the selection of his clothes, even the hiring of barbers to come to his office and cut his hair, his resources of energy were freed for the pursuit of his purposes. His life became an orgy of work.

The annoyances that plague busy executives had to be done away with. One of the worst was the telephone; he was continually being interrupted in the middle of one call by another urgent incoming message. Finally he had a new telephone setup installed. Under it, there were many lines into his secretary’s office but only one from hers into his; on the single telephone that remained on his desk there were no buttons.

Then there were intercoms; he liked to see his men face to face when he was giving them orders. His intercom was thrown out and in its place on his desk there was installed a panel with buttons that, when pressed, triggered a harsh buzz in the offices of his top executives. When the buzzer sounded in an executive’s office, he was expected to drop everything and get to Moses’ office fast.

A third feature of Moses’ office was his desk. It wasn’t a desk but rather a large table. The reason was simple: Moses did not like to let prob-lems pile up. If there was one on his desk, he wanted it disposed of im-mediately.

And there was another advantage: when your desk was a table, you could have conferences at it without even getting up.

And no matter how thin his remarkable capacity for work seemed stretched in the evening, a night’s sleep never failed to restore its resiliency

As much as any other quality, it was an ability to pick and organize men that enabled Moses to handle so brutal a workload.

Becoming recognized by public officials as an elite cadre within the ranks of the state’s civil servants and had already been given the name “Moses Men.” · Once they had proven themselves to him, Moses took pains with their training. They were, most of them, engineers and architects, and he was con-stantly distressed with their weakness in the use of the English language. So he taught them to write. Like a high-school English teacher, he gave them reports to write and letters to draft for his signature and then he corrected the reports and letters and had the authors redo them-sometimes over and over again.

Their purpose was to get public projects built, he would tell them, and to get them built they had to know how to persuade people of their worth-and the key to persuading people was to keep their arguments simple

“The first thing you’ve got to learn,” he said, “is that no one is interested in plans.

No one is interested in details. The first thing you’ve got to learn is to keep your presentations simple.”

Moses taught his men not to waste time. He didn’t want engineers wasting time debating legal points or lawyers discussing engineering problems.

If a legal problem arose at a staff meeting and an engineer ventured an opinion on it, he would cut him short with a curt “Stop practicing law. Leave that to the lawyers.”

He even taught them social graces so that they could dine with men in positions of power.

Those who didn’t break were rewarded. Advancement was rapid.

And he had the knack, the knack of the great executive, of delegating author-ity completely. His men learned that once a policy in their area of authority had been hammered out by Moses, the details of implementing that policy were strictly up to them; all their boss cared about was that they get it done.

They therefore had considerable power of their own, and this was incentive to those of them who wanted power.

The rewards Moses offered his men were not only power and money.

If they gave him loyalty, he returned it manyfold.

And the most valued reward-the thread that bound his men most closely to him-was still more intangible. “We were caught up in his sense of purpose,” Latham explained. “He made you feel that what we were doing together was tremendously important for the public, for the welfare of people.” The purposes were, after all, the purposes for which they had been trained. They were engineers and architects; engineers and architects want to build, and all Moses’ efforts were aimed at building.

Moses was playing by the rules of power now and one of the first of those rules is that when power meets greater power, it does not oppose but attempts to compromise.

Publicly, Moses never stopped excoriating the Long Island millionaires. But in private, many of them were coming to consider him quite a reasonable fellow to deal with.

Regard for power implies disregard for those without power.

Robert Moses had offered men of wealth and influence bridges across the parkway so that there would be no inter-ference with their pleasures. But he wouldn’t offer James Roth a bridge so that there would be no interference with his planting.

16. The Featherduster

As he had done in the little world of Yale, Robert Moses had erected within New York State a power structure all his own, an agency ostensibly part of the state government but only minimally responsive to its wishes.

The structure might appear flimsy but it was shored up with buttresses of the strongest material available in the world of politics: public opinion. A Gover-nor-even a Governor who hated the man who dwelt within that structure-would pull it down at his own peril.

17. The Mother of Accommodation

Robert Moses’ “compromise” with the North Shore barons amounted to unconditional surrender. In later years, most of the barons would have disappeared from the Long Island scene. The names of most of them would be unfamiliar to the new generations using the Northern State Parkway. But every twist and curve in that parkway-and, in particu-lar, the two great southward detours it makes around the Wheatley and Dix Hills-is a tribute to their power, and to the use to which they put it after they discovered the chink in Moses’ armor.

In Albany; where a legislative session is round after round of hastily formed alliances, trust in a man’s word is all-important; when a man promised his support on a bill, he could not later take it back; if he did so, the word on him would soon begin to circulate through the corridors of the capitol, and when discussing their relationships with him, legislators would say, “We deal in writing”-a phrase which, in Albany, was the ultimate insult. Al Smith could say, “When I give my word, it sticks.” Now, in the corridors of the capitol, many men were saying of the new Governor, “We deal in writing.”

But if Roosevelt gave Moses a hard time before doing so, he did nonetheless sign most of Moses’ bills. And although he may have hated Moses, during the four years of his Governorship he gradually increased, not decreased, Moses’ power.

And the explanation for the increase in Moses’ power during Roosevelt’s Governorship certainly wasn’t that he gave in like a good subordinate if he had a difference of opinion with his chief over a matter of policy. In fact, if his powers of persuasion were not sufficient to persuade Roosevelt to alter what Moses felt was an unwise decision, he did not hesitate to mobilize forces against the Governor.

Part of the explanation for Moses’ increased power was simply the breadth and depth of his knowledge of the government at whose head Roose-velt, with little preparation, suddenly had found himself. No one knew the vast administrative machinery the Governor was supposed to run better than this man the Governor hated. To a considerable extent, the machinery was his machinery.

Never, observers agreed, had any park been kept as clean as Jones Beach. College students hired for the summer were formed into “Courtesy Squads.” Patrolling the boardwalk, conspicuous in snow-white sailor suits and caps, they hurried to pick up dropped papers and cigarette butts while the droppers were still in the vicinity. They never reprimanded the culprits, but simply bent down, picked up the litter and put it in a trash basket. To make the resultant embarrassment of the litterers more acute, Moses refused to let the Courtesy Squaders use sharp-pointed sticks to pick up litter without stooping. He wanted the earnest, clean-cut college boys stooping, Moses explained to his aides. It would make the litterers more ashamed. He even is-sued the Courtesy Squaders large cloths so that they could wipe from the boardwalk gobs of spittle. His methods worked. As one writer put it: “You will feel like a heel if you so much as drop a gum wrapper.”

Thinking of his national image, not yet aware that liberal public spending might be a way to cushion the effects of the Depression, the Governor was anxious not to give opponents the chance to portray him as a big spender. By the end of 1930, moreover, state revenues had been so slashed by the Depression that the state budget was quiveringly taut. Throughout his second term he was continually pressing his cabinet members to cut costs. There was constant friction over Moses’ budget requests.

But in these battles with the Governor, Moses played the popularity that was his trump card for all it was worth. In fact, so sure was he-and he was right-that Roosevelt was afraid he would resign that he began using the technique, when Roosevelt crossed him on major issues, of threatening to do so.

A similar threat had been strikingly ineffective when made to Ed Richards beside the swimming pool at Yale. But given the fact of his tremen-dous popularity, it was very effective now.

“You can get an awful lot of good done in the world if you’re willing to let someone else take the credit for it.”

And if accomplishment, and willingness to share the credit for that accomplishment, was part of the explanation for the increase in Moses’ power under a Governor who had no inclination to increase it, the accomplishment helped explain this contradiction in other ways, too.

One way is that no Governor could sit in the Executive Chamber long without discovering just how hard-how incredibly hard-it was, even for a Governor, to get things, big things, done. No Governor, having made this discovery, could look at what Robert Moses had gotten done without being impressed, without feeling admiration for his ability, without a recognition of his extraordinary capacity as a public servant.

Another way is that accomplishment proves the potential for more accomplishment. The man who gets things done once can get things done _again.

Furthermore, he was trapped, as all politicians in elected executive offices are trapped, by the inexorable equation of de-mocracy and public works. Elections come every two years, or four, and the official who wants re-election needs a record of accomplishment on which to run.

It is no good still to be laying cornerstones on Election Day. By then, a public official in executive office must have ribbons he can cut, monuments to which he can point with pride. This is a requirement established by democracy as it has evolved in America, yet the realities of the democratic process in America make it almost impossible to get a road, a bridge, a housing project, a bathhouse or a park approved and built in two years–or four.

He loves the public, but not as people. The public is just the public.

It’s a great amorphous mass to him; it needs to be bathed, it needs to be aired, it needs recreation, but not for personal reasons-just to make it a better public.

A quotation from Shakespeare that he selected for an epigraph on the menu’s cover:

Politics is a thieves’ game.

Those who stay in it long enough are invariably robbed.

18. New York City Before Robert Moses

The city’s government did little to help its people.

The will to help was not the force that drove that government. That force was greed. During the fifteen years in which Red Mike Rylan and then Beau James Walker had been Chief Magistrate of America’s greatest city, the Tammany leaders who served under them had seemed motivated pri-marily by the desire to siphon the city’s vast resources into a vast trough on which they could batten.

In New York City under Tammany Hall, the test for employment on a federal project was generally politics rather than need; most applicants had to be cleared by their local Tammany leader; one leader boasted, “This is how we make Democrats.”

Even had the city wanted to help its people, it would have been unable to.

The Depression had forced New York to total up at last the cost of its Rake’s Progress under the Hylan and Walker administrations.

Although Walker and O’Brien attempted to do so, it was a misleading oversimplification to blame the Depression for all of New York’s problems.

The truth was that the city had been falling further and further behind in the race to meet the needs of its people in good times as well as bad, and under reform as well as Tammany administrations.

The gap between the city’s physical plant and the increasing needs of its expanding population had, then, been widening in virtually all areas of municipal responsibility.

It wasn’t what the Depression did to existing parks that most worried New York’s reformers. however; they were more concerned about its effect on the city’s plans to acquire new ones.

Moses gave the reformers something as valuable as his organiza-tion. He gave them his vision.

Roosevelt’s successor as Governor, Herbert H. Lehman, deeply re-spected Moses. Says one man who served as an adviser to both: “Roosevelt saw Jones Beach in terms both of people swimming and in terms of the political gains that could come from those people swimming. Herbert Leh-man thought only of helping people to go swimming and be happy. And he felt that no one could do that job better than Robert Moses.” Within a month after Lehman took office in January 1933, he handed to Moses even more power than Roosevelt had given him.

19. To Power in the City

The attitude of the reformers toward Moses was understandable. Not only had he fought in so many causes in which they believed; he had triumphed. Reformers who had learned through bitter, repeated experience the difficulty of translating ideas into realities were almost in awe of his success in doing so.

The reformers didn’t know the details of those triumphs. They were not, after all, on the inside of state government, where Moses’ power plays had been executed, and they knew nothing of his methods. If there had been a change in Robert Moses, none but a handful of them had even an inkling of it, and those who had seen glimpses of the change had, like Childs, been charmed into forgetting them by a Moses who needed their continuing support. They attributed Moses’ arrogance to brilliance, his impatience to zeal.

The reform movement of New York City had wanted Robert Moses for mayor. Of all the influential reformers, only one had been firmly opposed to him. Given the almost certain success in 1933 of a Fusion ticket headed by so popular a candidate, it is hardly an overstatement to say that only one man had stood between Moses and the mayoralty, between Moses and supreme power in the city. But that man had stood fast; at the last moment, as Moses must have felt the prize securely within his grasp, it was denied him.

Moses’ radio speeches and printed statements burst above the murk of the city’s political battlefield like a Roman candle whose sparkle, coming from a shower of glittering, sharp-pointed barbs flung off by a graceful and witty malice, was both hard and brilliant.

And each statement contained praise for La Guardia couched in a prose that had to it a ring that sounded all the clearer above the dull clangor that is political strife in New York.

To produce good government in a bankrupt city, the first requirement was money.

“No man is big enough to serve two masters.” This was one reason why there was a law against the simultaneous holding of state and city jobs.

20. One Year

Moses had given these men their orders. They were to weed out-immediately-those headquarters employees who would not or could not work at the pace he demanded. The weeding out would be accomplished by making all employees work at that pace-immediately.

Moses was confronting the CWA.

Its officials were worried themselves about the demoralization of the 68,ooo relief workers in the parks. Moses told them that the first requirement for getting those men working on worthwhile projects was to provide them with plans. Blueprints in volume were needed, he said, and they were needed immediately. He must be allowed to hire the best architects and engineers available and he must be allowed to hire them fast. The CW A must forget about its policy of keeping expenditures for plans small to keep as much money as possible for salaries for men in the field. The agency must forget its policy that only unemployed men could be hired so that Moses could hire a good architect even if he was working as a ditch digger or was being kept on by his firm at partial salary. And the agency must drop its rule that no worker could be paid more than thirty dollars per week. The CW A refused:

rules were rules, it said. I quit, Moses said. La Guardia hastily intervened.

After seven days of haggling, the CW A surrendered.

Moses had found the men to do the shaping. Out of fear of losing them permanently to rivals, idle construction contractors were struggling to keep on salary their “field superintendents,” the foremen or “ramrods” whose special gift for whipping tough Irish laborers into line made them an almost irreplaceable asset. Pointing out that the CW A was not a rival and would probably go out of existence when business improved, Moses persuaded contractors throughout New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New Eng-land to give him their best ramrods, “the toughest you’ve got.”

He seemed to see opportunities everywhere.

I’m satisfied to make just a bare living if I can realize all my plans for these things I enjoy. I’m interested in cutting down the overhead and getting results, not in pay.

The purpose of a park, Moses had been telling his designers for years, wasn’t to overawe or impress; it was to encourage the having of a good time.

And the Triborough Bridge was finally being built.

Here was a project to kindle the imagination.

In size, its proportions were heroic. For all Moses’ previous construction feats, it dwarfed any other single enterprise he had undertaken. Its approach ramps would be so huge that houses-not only single-family homes but sizable apartment buildings-would have to be demolished by the hundreds to give them footing. Its anchorages, the masses of concrete in which its cables would be embedded, would be as big as any pyramid built by an Egyptian Pharaoh, its roadways wider than the widest roadways built by the Caesars of Rome.

Triborough was not a bridge so much as a traffic machine, the largest ever built.

The man who built the Triborough Bridge would be a man who conferred a great boon on the greatest city in the New World. He would be the man who tied that city together. In fact, since each of the three boroughs was as large as a city in its own right, the man who built the Triborough Bridge could be said to be performing a feat equal to tying together three cities.

Build Triborough, he felt, and the Long Island parks would at a stroke be made easily accessible from the entire New York metropolitan area.

Join islands to city and you would be creating a moated oasis at the city’s core.

The potentialities of the project, not only for transportation, but for recrea-tion, were awesome.

Moses had learned how to get things done and one way not to get things done in New York was to pick a fight with Hearst and his three newspapers.

He left the Manhattan terminus at 125th Street.

Robert Moses erected the complex of buildings that was the Central Park Zoo at least partly because of his devotion to Alfred E. Smith. He tore down another building in the park wholly because of that devotion.

He tore down Jimmy Walker’s Casino.

It was a case of revenge, pure and simple

21. The Candidate

THERE HAD BEEN A DAY in 1934 on which the cheering had stopped.

It was the day Robert Moses started running for Governor.

The identity of the man who offered Moses the nomination is perhaps the clearest proof of the inaccuracy of the portrait Moses had painted of himself as the foe of the forces of influence, privilege and wealth. For Trubee Davison was the acknowledged representative of those forces.

Davison was a key figure in the ranks of the Long Island robber barons. And Davison was taking an active interest in the selection of the gubernatorial nominee precisely because the barons felt that their influence and privilege and, to some extent, their wealth, were threatened.

It was important to the Interests that they control the state GOP. It was important for business reasons-the party was the Interests’ traditional protector in Albany-and it was important for reasons that went beyond business: the conservatism of these men of property, to whom property rights were sacred, was not only financial but ideological, and they viewed their party as a bulwark against heresy, against the increasing emphasis on human as opposed to property rights that characterized the philosophy of the three Democrats-Smith, Roosevelt and Lehman-who had usurped the Executive Chamber. Public reverence for their beliefs might be dying, but they would never surrender them. Not for nothing had journalists dubbed them “the Old Guard.”

His aggressiveness had, after all, turned out to be not the hostility of the radical, idealistic reformer to property and power but something quite the opposite, an expression of his regard for power, an acknowledgment of the fact that he had on his side, in the person of that uneducated, practically illiterate demagogue from the Fulton Fish Market, the one man in the state with power equal to theirs and therefore did not have to compromise with them. As soon as he no longer had this power behind him, he had changed, suddenly, dramatically and, to them, satisfyingly. He had proven understanding-sympathetic, in fact-to their desire to keep the rabble away from their estates; he had proven his sympathy, in their view, by his agreement to make the parkway not an accessway to parks on the North Shore but a “traffic bridge,” a chute, similar in principle to a cattle chute, on which the public would be shunted across the Gold Coast without being allowed to get off and contaminate it.

His receptivity to their demands for private parkway entrances and bridges had proven him to be what they called a “practical man,” a man willing to make accommodation with power.

Just as important to the Old Guard as this facet of Moses’ personality was the fact that the public didn’t know about it. Thanks to his genius for public relations, to the people he was still the fighter for parks and against privilege. And therefore if he was the Old Guard candidate against Seabury, the press would not be able to charge that the Old Guard-and the scandal-scarred utilities-were trying to keep control of the GOP. No one would believe Macy if he charged that Robert Moses was a front for the “power lobby.”

Then there was the press.

Most candidates attempt to woo reporters covering the campaign. It took Moses exactly one press conference to turn them icily frigid toward his candidacy.

This might have been surprising to those who had observed his long love affair with the press. But that love affair had endured only because he had never been exposed to the probing questioning to which reporters subject most public officials. His aides, who knew his sensitivity to even the most discreetly implied criticism, could have predicted what would happen when he was.

“Every time he opened his mouth, he lost ten thousand votes.”

His method of issue disposal, moreover, was not particularly convincing. It consisted of flat assertions

Lehman, advised by men who knew Moses well-Proskauer, Shientag and Moskowitz, for example-handled Moses just right. The Governor ignored the invitation to debate-and, to a large extent, he ignored Moses’ charges. In fact, to a large extent, he ignored Moses, sticking strictly to a discussion of the issues and his record as he campaigned earnestl

Moses’ response was to increase the violence of his attacks and the wildness of his accusations.

It wasn’t what Moses said that most antagonized voters; it was how he said it. He let his contempt for the public show.