Summary

A great book on the philosophy and emotional side of investing and all its nuances. Commentary throughout the book is great too. Not recommended for beginning investors, however, as the concepts and way of writing are quite advanced.

Key Takeaways

- “Experience is what you got when you didn’t get what you wanted.”

- Inefficiency is a necessary condition for superior investing.

- The upside potential for being right about growth is more dramatic, and the upside potential for being right about value is more consistent.

- No matter how good an investment sounds, if price has not yet been considered, you can’t know if it is a good investment.

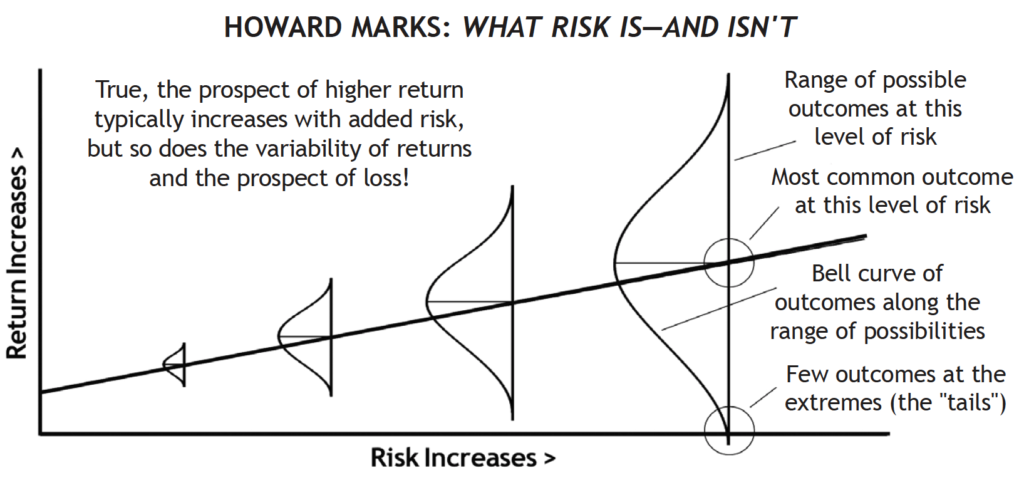

- Riskier investments are those for which the outcome is less certain. That is, the probability distribution of returns is wider.

- The risk of permanent capital loss is the only risk to worry about.

- The fact that something – in this case, loss – happened doesn’t mean it was bound to happen, and the fact that something didn’t happen doesn’t mean it was unlikely.

- The greatest risk doesn’t come from low quality or high volatility. It comes from paying prices that are too high.

- Loss is what happens when risk meets adversity.

- Cycles always prevail eventually.

- Our goal is to find underpriced assets. A good place to start is among things that are:

- Little known and not fully understood.

- Fundamentally questionable on the surface.

- Controversial, unseemly or scary.

- Deemed inappropriate for “respectable” portfolios.

- Unappreciated, unpopular and unloved.

- Trailing a record of poor returns.

- Recently the subject of disinvestment, not accumulation.

- Until one learns to identify the true source of success, one will be fooled by randomness.

- One way to maximize the asymmetry of risk and reward is to make sure you minimize risk. If you minimize the chance of loss in an investment, most of the other alternatives are good.

- Invest scared!

- Buying below value is the most dependable route to profit.

- An investor can obtain margin for error by:

- Insisting on tangible lasting value in the here and now;

- Buying only when price is well below value;

- Eschewing leverage;

- And diversifying.

- What it takes to deal with uncertainty:

- A feeling for the things that can happen,

- The relative likelihood of each,

- And whether an asset’s price (and thus the potential for gains from that price) provides adequate potential reward for bearing the uncertainty that is present.

What I got out of it

A book focused on the philosophy of investing. Investing is ultimately an emotional and mental game, after all.

At the end of the book, I felt I had read the same content multiple times, but each time Marks shone a light on it from a different angle, increasing my understanding of the subject.

In my opinion, this is the best book on understanding risk in investing (chapters 5, 6 and 7).

Definitely not a book for beginners nor for people looking for actionable material.

For the more practically-oriented, read Beating The Street by Peter Lynch or The Little Book of Valuation by Aswath Damodaran.

- Summary

- Key Takeaways

- Summary Notes

- Introduction

- Second-Level Thinking

- Understanding Market Efficiency (and its Limitations)

- Value

- The Relationship Between Price and Value

- Understanding Risk

- Recognizing Risk

- Controlling Risk

- Being Attentive to Cycles

- Awareness of the Pendulum

- Combating Negative Influences

- Contrarianism

- Finding Bargains

- Patient Optimism

- Knowing What You Don’t Know

- Having A Sense For Where We Stand

- Appreciating The Role Of Luck

- Investing Defensively

- Avoiding Pitfalls

- Adding Value

- Reasonable Expectations

- Pulling It All Together

Summary Notes

Introduction

“What have been the keys to your success?” My answer is simple: an effective investment philosophy, developed and honed over more than four decades and implemented conscientiously by highly skilled individuals who share culture and values.

A philosophy has to be the sum of many ideas accumulated over a long period of time from a variety of sources.

“Experience is what you got when you didn’t get what you wanted.” – Howard Marks

Second-Level Thinking

It is essential that one’s investment approach be intuitive and adaptive rather than be fixed and mechanistic.

First-level thinking is simplistic and superficial, and just about everyone can do it (a bad sign for anything involving an attempt at superiority). All the first-level thinker needs is an opinion about the future.

Second-level thinking is deep, complex and convoluted. The second-level thinker takes a great many things into account.

- What is the range of likely future outcomes?

- Which outcome do I think will occur?

- What’s the probability I’m right?

- What does the consensus think?

- How does my expectation differ from the consensus?

- How does the current price for the asset comport with the consensus view of the future, and with mine?

- Is the consensus psychology that’s incorporated in the price too bullish or bearish?

- What will happen to the asset’s price if the consensus turns out to be right, and what if I’m right?

Extraordinary performance comes only from correct nonconsensus forecasts, but nonconsensus forecasts are hard to make, hard to make correctly and hard to act on.

To achieve superior investment results, you have to hold nonconsensus views regarding value, and they have to be accurate.

Understanding Market Efficiency (and its Limitations)

In January 2000, Yahoo sold at $237. In April 2001 it was at $11. Anyone who argues that the market was right both times has his or her head in the clouds; it has to have been wrong on at least one of those occasions. But that doesn’t mean many investors were able to detect and act on the market’s error.

Psychological influences are a dominating factor governing investor behaviour. They matter as much as – and at times more than – underlying value in determining securities prices.

Some asset classes are quite efficient, in most of these:

- The asset class is widely known and has a broad following.

- The class is socially acceptable, not controversial or taboo.

- The merits of the class are clear and comprehensible, at least on the surface.

- Information about the class and its components is distributed widely and evenly.

Note that most of these characteristics are not permanent.

Inverting the above conditions yields a test of market inefficiency. For instance, in the first case, if an asset is not widely known and broadly followed, it might be inefficiently priced; in the second case, if an asset is controversial, taboo, or socially unacceptable, it might be inefficiently priced; and so on for each of the other two cases.

Second-level thinkers know that, to achieve superior results, they have to have an edge in either information or analysis, or both.

Ask yourself: “And who doesn’t know that?”

Human beings are not clinical computing machines. Rather, most people are driven by greed, fear, envy and other emotions that render objectivity impossible and open the door for significant mistakes.

Whereas investors are supposed to be open to any asset – and to both owning it and being short – the truth is very different.

Ask yourself: have mistakes and mispricings been driven out through investors’ concerted efforts, or do they still exist, and why?

Think of it this way:

- Why should a bargain exist despite the presence of thousands of investors who stand ready and willing to bid up the price of anything that’s too cheap?

- If the return appears so generous in proportion to the risk, might you be overlooking some hidden risk?

- Why would the seller of the asset be willing to part with it at a price from which it will give you an excessive return?

- Do you really know more about the asset than the seller does?

- If it’s such a great proposition, why hasn’t someone else snapped it up?

Inefficiency is a necessary condition for superior investing.

Value

For investing to be reliably successful, an accurate estimate of intrinsic value is the indispensable starting point.

“Warren Buffett says that the best investment course would teach just two things well: How to value an investment and how to think about market price movements.” – Joel Greenblatt

Random walk hypothesis says a stock’s past price movements are of absolutely no help in predicting future movements. In other words, it’s a random process.

Intelligent investing has to be built on estimates of intrinsic value. Those estimates must be derived rigorously, based on all of the available information.

The difference between the two principal schools of investing:

- Value investors buy stocks (even those whose intrinsic value may show little growth in the future) out of conviction that the current value is high relative to the current price.

- Growth investors buy stocks (even those whose current value is low relative to their current price) because they believe the value will grow fast enough in the future to produce substantial appreciation.

Thus the choice isn’t really between value and growth, but between value today and value tomorrow.

“Buffett looks for “good” businesses at an attractive price. The concept of growth is incorporated into the calculation of value.” – Joel Greenblatt

“If you are right about the business, time can reduce the cost of overpaying.” – Christopher Davis

The upside potential for being right about growth is more dramatic, and the upside potential for being right about value is more consistent.

There are two essential ingredients for profit in a declining market:

- You have to have a view on intrinsic value.

- You have to hold that view strongly enough to be able to hang in and buy even as price declines suggest that you’re wrong.

- Oh yes, you have to be right too.

The Relationship Between Price and Value

No matter how good an investment sounds, if price has not yet been considered, you can’t know if it is a good investment.

If your estimate of intrinsic value is correct, over time an asset’s price should converge with its value. Remember this when the market acts emotionally over the short term.

The discipline that is most important is not accounting or economics, but psychology.

People should like something less when its price rises, but in investing they often like it more.

Using leverage – buying with borrowed money – doesn’t make anything a better investment or increase the probability of gains. It merely magnifies whatever gains or losses may materialize. And it introduces the risk of ruin if a portfolio fails to satisfy a contractual value test and lenders can demand their money back at a time when prices and illiquidity are depressed.

Buying at a discount from intrinsic value and having the asset’s price move toward its value doesn’t require serendipity; it just requires that market participants wake up to reality. When the market’s functioning properly, value exerts a magnetic pull on price.

Understanding Risk

Going beyond determining whether he or she can bear the absolute amount of risk that is attendant, the investor’s second job is to determine whether the return on a given investment justifies taking the risk.

In order to reach a conclusion, they have to have some idea about how much risk their managers took.

Risker investments absolutely cannot be counted on to deliver higher returns. Why not? It’s simple: if riskier investments reliably produced higher returns, they wouldn’t be riskier!

The correct formulation is that in order to attract capital, riskier investments have to offer the prospect of higher returns.

A helpful way to think about the probability distribution of future returns is to remember that the outcome distribution of these possible returns is not, in reality, normally distributed.

Riskier investments are those for which the outcome is less certain. That is, the probability distribution of returns is wider. When priced fairly, riskier investments should entail:

- Higher expected returns;

- The possibility of lower returns;

- In some cases the possibility of loss.

The risk of permanent capital loss is the only risk to worry about.

Risk isn’t just about losing money or volatility. It’s being unable when needed to turn an investment into cash at a reasonable price. This, too, is a personal risk.

The most dangerous investment conditions generally stem from psychology that’s too positive. For this reason, fundamentals don’t have to deteriorate in order for losses to occur; a downgrading of investor opinion will suffice. High prices often collapse of their own weight.

The greatest risk in these low-luster bargains lies in the possibility of underperforming in heated bull markets. That’s something the risk-conscious value investor is willing to live with.

How do you measure risk?

- It clearly is nothing but a matter of opinion: hopefully an estimated, skilful estimate of the future, but still just an estimate.

- The standard for quantification is nonexistent.

“The relationship between different kinds of investments and the risk of loss is entirely too indefinite, and too variable with changing conditions, to permit of sound mathematical formulation.” – Security Analysis 2nd edition, Ben Graham and David Dodd

The bottom line is that, looked at prospectively, much of risk is subjective, hidden and unquantifiable.

Sharpe ratio: this calculation seems serviceable for public market securities that trade and price often; there is some logic, and it truly is the best we have.

For private assets lacking market prices – like real estate and whole companies – there’s no alternative to subjective risk adjustment.

The fact that something – in this case, loss – happened doesn’t mean it was bound to happen, and the fact that something didn’t happen doesn’t mean it was unlikely.

The possibility of a variety of outcomes means we mustn’t think of the future in terms of a single result but rather as a range of possibilities. The best we can do is fashion a probability distribution that summarizes the possibilities and describes their relative likelihood. Some of the greatest losses arise when investors ignore improbable possibilities.

The key to understanding risk: it’s largely a matter of opinion.

People overestimate their ability to gauge risk and understand mechanisms they’ve never before seen in operation.

Recognizing Risk

Risk means uncertainty about which outcome will occur and about the possibility of loss when the unfavourable ones do.

The greatest risk doesn’t come from low quality or high volatility. It comes from paying prices that are too high.

The value investor thinks of high risk and low prospective return as nothing but two sides of the same coin, both stemming primarily from high prices.

There are few things as risky as the widespread belief that there’s no risk.

Risk cannot be eliminated; it just gets transferred and spread.

Each investment has to compete with others for capital.

People vastly overestimate their ability to recognize risk and underestimate what it takes to avoid it; thus, they accept risk unknowingly and in so doing contribute to its creation. That’s why it’s essential to apply uncommon, second-level thinking to the subject.

Investment risk resides most where it is least perceived, and vice versa.

This paradox exists because most investors think quality, as opposed to price, is the determinant of whether something’s risky.

Controlling Risk

Loss is what happens when risk meets adversity. Risk is the potential loss if things go wrong. As long as things go well, loss does not arise.

The important thing here is the realization that risk may have been present even though loss didn’t occur. Therefore, the absence of loss does not necessarily mean the portfolio was safely constructed.

How do you enjoy the full gain in up markets while simultaneously being positioned to achieve superior performance in down markets? By capturing the up-market gain while bearing below-market risk.

Controlling the risk in your portfolio is a very important and worthwhile pursuit. The fruits, however, come only in the form of losses that don’t happen. Such what-if calculations are difficult in placid times. This is the ultimate paradox of risk management.

What does it mean to intelligently bear risk for profit? Take the example of life insurance:

- It’s risk they’re aware of.

- It’s risk they can analyze.

- It’s risk they can diversify.

- It’s risk they can be sure they’re well paid to bear.

It’s easy to say they should have made more conservative assumptions. But how conservative?

Risk control is the best route to loss avoidance. Risk avoidance, on the other hand, is likely to lead to return avoidance as well.

Investors’ results will be determined more by how many losses they have, and how bad they are, than by the greatness of their winners. Skilful risk control is the market of the superior investor.

Being Attentive to Cycles

Cycles always prevail eventually. Nothing goes in one direction forever. Trees don’t grow to the sky. Few things go to zero.

Two investment rules to remember:

- Rule number one: most things will prove to be cyclical.

- Rule number two: some of the greatest opportunities for gain and loss come when other people forget rule number one.

Objective factors do play a large part in cycles, of course – factors such as quantitative relationships, world events, environmental changes, technological developments and corporate decisions. But it’s the application of psychology to these things that causes investors to overreact or underreact, and thus determines the amplitude of the cyclical fluctuations.

Trends create the reasons for their own reversal.

Success carries within itself the seeds of failure, and failure the seeds of success.

Awareness of the Pendulum

The greed/fear cycle is caused by changing attitudes toward risk.

When investors in general are too risk-tolerant, security prices can embody more risk than they do return. When investors are too risk-averse, prices can offer more return than risk.

Extreme market behaviour will reverse.

Combating Negative Influences

The desire for more, the fear of missing out, the tendency to compare against others, the influence of the crowd and the dream of the sure thing – these factors are near universal.

Inefficiencies – mispricings, misperceptions, mistakes that other people make – provide potential opportunities for superior performance. Exploiting them is, in fact, the only road to consistent outperformance.

Psychological tendencies that undermine investors’ efforts and contribute to investor error (for a great overview of all of our psychological tendencies, read The Psychology of Human Misjudgment by Charlie Munger):

- The desire for money, especially as it morphs into greed.

- The counterpart of greed: fear.

- People easily engage in willing suspension of disbelief and have a tendency to dismiss logic, history and time-honoured norms.

- Tendency to conform to the view of the herd rather than resist – even when the herd’s view is clearly cockeyed.

- Envy.

- Capitulation, a regular feature of investor behaviour late in cycles. Investors hold to their convictions as long as they can, but when the economic and psychological pressures become irresistible, they surrender and jump on the bandwagon.

The gravest market losses have their genesis in psychological errors, not analytical miscues.

What weapons might you marshal on your side to increase your odds?

- A strongly held sense of intrinsic value.

- Insistence on acting as you should when price diverges from value.

- Enough conversance with past cycles – gained at first from reading and talking to veteran investors, and later through experience – to know that market excesses are ultimately punished, not rewarded.

- A thorough understanding of the insidious effect of psychology on the investing process at market extremes.

- A promise to remember that when things seem “too good to be true,” they usually are.

- Willingness to look wrong while the market goes from misvalued to more misvalued (as it invariably will).

- Like-minded friends and colleagues from whom to gain support (and for you to support).

Contrarianism

The ultimately most profitable investment actions are by definition contrarian: you’re buying when everyone else is selling (and the price is thus low) or you’re selling when everyone else is buying (and the price is high).

If everyone likes it, it’s probably because it has been doing well. Most people seem to think outstanding performance to date presages outstanding future performance. Actually, it’s more likely that outstanding performance to date has borrowed from the future and thus presages subpar performance from here on out.

Superior investors know – and buy – when the price of something is lower than it should be.

There are two primary elements in superior investing:

- Seeing some quality that others don’t see or appreciate (and that isn’t reflected in the price).

- Having it turn out to be true (or at least accepted by the market).

The herd applies optimism at the top and pessimism at the bottom. Thus, to benefit, we must be sceptical of the optimism that thrives at the top, and skeptical of the pessimism that prevails at the bottom.

By the time the knife has stopped falling, the dust has settled and the uncertainty has been resolved, there’ll be no great bargains left. When buying something has become comfortable again, its price will no longer be so low that it’s a great bargain.

That’s why the concept of intrinsic value is so important.

Finding Bargains

The process of intelligently building a portfolio of buying the best investments, making room for them by selling lesser ones, and staying clear of the worst.

The raw materials for the process consist of…

- A list of potential investments

- Estimates of their intrinsic value

- A sense of how their prices compare with their intrinsic value

- An understanding of the risks involved in each, and of the effect their inclusion would have on the portfolio being assembled

Investment is the discipline of relative selection.

The tendency to mistake objective merit for investment opportunity, and the failure to distinguish between good assets and good buys, get most investors into trouble.

Bargains usually are based on irrationality or incomplete understanding.

Our goal is to find underpriced assets. A good place to start is among things that are:

- Little known and not fully understood.

- Fundamentally questionable on the surface.

- Controversial, unseemly or scary.

- Deemed inappropriate for “respectable” portfolios.

- Unappreciated, unpopular and unloved.

- Trailing a record of poor returns.

- Recently the subject of disinvestment, not accumulation.

Patient Optimism

You’ll do better if you wait for investments to come to you rather than go chasing after them. You tend to get better buys if you select from the list of things sellers are motivated to sell rather than start with a fixed notion as to what you want to own. An opportunist buys things because they’re offered at bargain prices.

If we call the owner and say, “You own X and we want to buy it.” the price will go up. But if the owner calls us and says, “We’re stuck with X and we’re looking for an exit,” the price will go down.

“Investing is the greatest business in the world because you never have to swing. You stand at the plate; the pitcher throws you General Motors at 47! U.S. Steel at 39! And nobody calls a strike on you. There’s no penalty except opportunity. All day you wait for the pitch you like; then, when the fielders are asleep, you step up and hit it.” – Warren Buffett

The key during a crisis is to be…

- Insulated from the forces that require selling.

- Positioned to be a buyer instead.

To satisfy those criteria, an investor needs the following things: staunch reliance on value, little or no use of leverage, long-term capital and a strong stomach.

Knowing What You Don’t Know

Forecasts are of very little value.

Having A Sense For Where We Stand

In the world of investing, nothing is as dependable as cycles. Fundamentals, psychology, prices and returns will rise and fall, presenting opportunities to make mistakes or to profit from the mistakes of others. They are the givens.

Ask yourself:

- Are investors optimistic or pessimistic?

- Do the media talking heads say the markets should be piled into or avoided?

- Are novel investment schemes readily accepted or dismissed out of hand?

- Are securities offerings and fund openings being treated as opportunities to get rich or possible pitfalls?

- Has the credit cycle rendered capital readily available or impossible to obtain?

- Are price/earnings ratios high or low in the context of history, and are yield spreads tight or generous?

The seven scariest words in the world for the thoughtful investor: too much money chasing too few deals.

When buyers compete to put large amounts of capital to work in a market, prices are bid up relative to value, prospective returns shrink and risk rises. It’s only when buyers predominate relative to sellers that you can have highly overpriced assets.

If you deal in a commodity and want to sell more of it, there’s generally one way to do so: cut your price.

It helps to think of money as a commodity just like those others. Everyone’s money is pretty much the same. Yet institutions seeking to add to loan volume, and private equity funds and hedge funds seeking to increase their fees, all want to move more of it. So if you want to place more money – that is, get people to go to you instead of your competitors for their financing – you have to make your money cheaper.

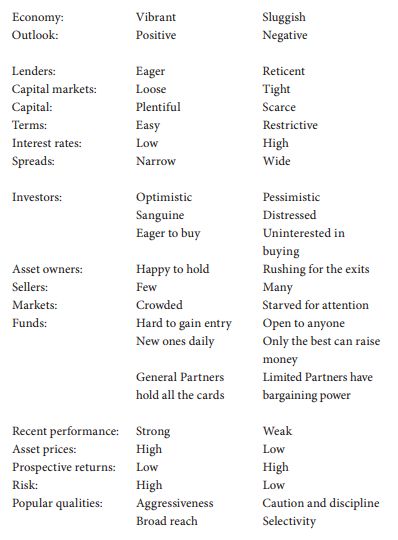

The Poor Man’s Guide To Market Assessment

Here’s a list of market characteristics. For each pair, check off the one you think is most descriptive of today. And if you find that most of your checkmarks are in the left-hand column, hold on to your wallet.

Appreciating The Role Of Luck

Learn to be honest with yourself about your successes and failures. Learn to recognize the role luck has played in all outcomes. Learn to decide which outcomes came about because of skill and which because of luck. Until one learns to identify the true source of success, one will be fooled by randomness.

The keys to profit are aggressiveness, timing and skill, and someone who has enough aggressiveness at the right time doesn’t need much skill.

A list of things that can easily be mistaken for one another:

- Luck vs Skill

- Randomness vs Determinism

- Probability vs Certainty

- Belief, conjecture vs Knowledge, certitude

- Theory vs Reality

- Anecdote, coincidence vs Causality, law

- Survivorship bias vs Market outperformance

- Lucky idiot vs Skilled investor

In the long run, there’s no reasonable alternative to believing that good decisions will lead to investment profits. In the short run, however, we must be stoic when they don’t.

Short-term gains and short-term losses are potential impostors, as neither is necessarily indicative of real investment ability (or the lack thereof).

We should spend our time trying to find value among the knowable – industries, companies and securities – rather than base our decisions on what we expect from the less-knowable macro world of economies and broad market performance.

We have to practice defensive investing, since many of the outcomes are likely to go against us. It’s more important to ensure survival under negative outcomes than it is to guarantee maximum returns under favourable ones.

Given the highly indeterminate nature of outcomes, we must view strategies and their results – both good and bad – with suspicion until proven out over a large number of trials.

Investing Defensively

When asked for investment advice, first try to understand their attitude toward risk and return.

Ask: “Which do you care about more, making money or avoiding losses?”

The choice between offense and defense investing should be based on how much the investor believes is within his or her control.

Oaktree’s preference for defense is clear. In good times, we feel it’s okay if we just keep up with the indices (and in the best of times we may even lag a bit). But even average investors make a lot of money in good times, and I doubt many managers get fired for being average in up markets. Oaktree’s portfolios are set up to outperform in bad times, and that’s when we think outperformance is essential.

Rather than doing the right thing, the defensive investor’s main emphasis is on not doing the wrong thing.

There are two principal elements in investment defense:

- The exclusion of losers from portfolios. This is best accomplished by conducting extensive due diligence, applying high standards, demanding a low price and generous margin for error and being less willing to bet on continued prosperity, rosy forecasts and developments that may be uncertain.

- The avoidance of poor years and, especially, exposure to meltdown in crashes. In addition to the ingredients described previously that help keep individual losing investments from the portfolio, this aspect of investment defense requires thoughtful portfolio diversification, limits on the overall riskiness borne, and a general tilt toward safety.

Concentration and leverage are two examples of offense.

““Margin of safety” and “Mr. Market” are the two ideas that Buffett refers to as Graham’s greatest contributions to the investing world.” – Joel Greenblatt

Despite the presence of uncertainty, many investors try to select the ideal strategy through which to maximize return. But if instead, we acknowledge the existence of uncertainty, we should insist on building in a generous margin of safety. That’s what keeps your result tolerable when undesirable outcomes materialize.

It’s not hard to make loans that will be repaid if conditions remain as they are – e.g., if there’s no recession and the borrower holds on to his or her job. But what will enable that loan to be repaid even if conditions deteriorate? Once again, margin for error.

The prudent lender’s reward comes only in bad times, in the form of reduced credit losses. The lender who insists on margin for error won’t enjoy the highest highs but will also avoid the lowest lows.

Achieving gains usually has something to do with being right about events that are on the come, whereas losses can be minimized by ascertaining that tangible value is present, the herd’s expectations are moderate and prices are low.

Distinguishing yourself as a bond investor isn’t a matter of which paying bonds you hold, but largely of whether you’re able to exclude bonds that don’t pay.

One way to maximize the asymmetry of risk and reward is to make sure you minimize risk. If you minimize the chance of loss in an investment, most of the other alternatives are good.

Many investment managers end up out of the game because they strike out too often – not because they don’t have enough winners, but because they have too many losers.

The cautious seldom err or write great poetry.

The avoidance of losses and terrible years is more easily achieved than repeated greatness, and thus risk control is more likely to create a solid foundation for a superior long-term track record. Investing scared, requiring good value and a substantial margin for error, and being conscious of what you don’t know and can’t control are hallmarks of the best investors.

In investing, almost everything is a two-edged sword.

The only exception is genuine personal skill.

Invest scared!

Worry about the possibility of loss. Worry that there’s something you don’t know. Worry that you can make high-quality decisions but still be hit by bad luck or surprise events.

Avoiding Pitfalls

An investor needs to do very few things right as long as he avoids big mistakes.

One type of analytical error is “failure of imagination”: being unable to conceive of the full range of possible outcomes or not fully understanding the consequences of the more extreme occurrences.

In other words: errors of quantification versus errors of judgment.

Psychological or emotional sources of error: greed and fear; willingness to suspend disbelief and scepticism; ego and envy; the drive to pursue high returns through risk-bearing; and the tendency to overrate one’s foreknowledge.

Another important pitfall is the failure to recognize market cycles and manias and move in the opposite direction.

Beware herd psychology.

The financial crisis occurred largely because never-before-seen events collided with risky, levered structures that weren’t engineered to withstand them.

The failure to correctly anticipate co-movement within a portfolio is a critical source of investment error.

How are investors harmed by psychological tendencies:

- By succumbing to them.

- By participating unknowingly in markets that have been distorted by others’ succumbing.

- By failing to take advantage when those distortions are present.

Beware the “it’s different this time” belief.

There’s always a rational explanation why some eighth wonder of the world will work in the investor’s favour. The explainer usually forgets to mention that:

- The new phenomenon would represent a departure from history.

- It requires things to go right.

- Many other things could happen instead.

- Many of those things might be disastrous.

The keys to investment success lie in observing and learning.

What we learn from a crisis – or ought to:

- Too much capital availability makes money flow to the wrong places.

- When capital goes where it shouldn’t, bad things happen.

- When capital is in oversupply, investors compete for deals by accepting low returns and a slender margin for error.

- This is one of the reasons we always think in terms of earnings yield (which is just the inverse of P/E) rather than in P/Es; doing so allows for easy comparison to fixed-income alternatives.

- Widespread disregard for risk creates great risk.

- Inadequate due diligence leads to investment losses.

- In heady times, capital is devoted to innovative investments, many of which fail the test of time.

- Hidden fault lines running through portfolios can make the prices of seemingly unrelated assets move in tandem.

- Psychological and technical factors can swamp fundamentals.

- Markets change, invalidating models.

- Leverage magnifies outcomes but doesn’t add value.

- Excesses contract.

Most of these lessons can be reduced to just one: be alert to what’s going on around you with regard to the supply/demand balance for investable funds and the eagerness to spend them.

The formula for error is simple, but the ways it appears are infinite. The usual ingredients:

- Data or calculation error in the analytical process leads to an incorrect appraisal of value.

- The full range of possibilities or their consequences is underestimated.

- Greed, fear, envy, ego, suspension of disbelief, conformity or capitulation, or some combination of these, moves to an extreme.

- As a result, either risk-taking or risk avoidance becomes excessive.

- Prices diverge significantly from value.

- Investors fail to notice this divergence, and perhaps contribute to its furtherance.

When there’s nothing particularly clever to do, the potential pitfall lies in insisting on being clever.

Adding Value

Only skill can be counted on to add more in propitious environments than it costs in hostile ones.

The formula for explaining portfolio performance (y) is as follows:

y = 𝛂+𝛃x

Here x is the return of the market. The market-related return of the portfolio is equal to its beta times the market return, and alpha (skill-related return) is added to arrive at the total return.

Risk-adjusted return holds the key, even though – since risk other than volatility can’t be quantified – it is best assessed judgmentally, not calculated scientifically.

Investors who lack skill simply earn the return of the market and the dictates of their style.

The performance of investors who add value is asymmetrical. The percentage of the market’s gain they capture is higher than the percentage of loss they suffer.

Asymmetry – better performance on the upside than on the downside relative to what your style alone would produce – should be every investor’s goal.

Reasonable Expectations

Every investment effort should begin with a statement of what you’re trying to accomplish. The key questions are…

- What your return goal is

- How much risk you can tolerate

- How much liquidity you’re likely to require in the interim.

Pulling It All Together

The best foundation for a successful investment – or a successful investment career – is value. You must have a good idea of what the thing you’re considering buying is worth. There are many components to this and many ways to look at it.

To oversimplify:

- There’s cash on the books and the value of the tangible assets;

- The ability of the company or asset to generate cash;

- And the potential for these things to increase.

To achieve superior investment results, your insight into value has to be superior.

Thus you must:

- Learn things others don’t;

- See things differently;

- Or do a better job at analyzing them – ideally, all three.

The relationship between price and value holds the ultimate key to investment success. Buying below value is the most dependable route to profit.

The power of psychological influences must never be underestimated. Greed, fear, suspension of disbelief, conformism, envy, ego and capitulation are all part of human nature, and their ability to compel action is profound, especially when they’re at extremes and shared by the herd.

Buying based on strong value, low price relative to value, and depressed general psychology is likely to provide the best results. Even then, however, things can go against us for a long time before turning as we think they should.

“Being too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong.”

Most investors are simplistic, and preoccupied with the chance for return. Some gain further insight and learn that it’s as important to understand risk as it is return. But it’s the rare investor who achieves the sophistication required to appreciate correlation, a key element in controlling the riskiness of an overall portfolio.

Diversification is effective only if portfolio holdings can be counted on to respond differently to a given development in the environment.

Risk control is about not doing the wrong thing.

An investor can obtain margin for error by:

- Insisting on tangible lasting value in the here and now;

- Buying only when price is well below value;

- Eschewing leverage;

- And diversifying.

The more micro your focus, the greater the likelihood you can learn things others don’t.

What it takes to deal with uncertainty:

- A feeling for the things that can happen,

- The relative likelihood of each,

- And whether an asset’s price (and thus the potential for gains from that price) provides adequate potential reward for bearing the uncertainty that is present.