Summary

A recount of the American banana industry from the late 19th century to the mid 20th century, with a focus on the rise and fall of Sam Zemurray (Sam the Banana Man). Long-winded, but many lessons for entrepreneurs.

Key Takeaways

- Sam would develop a philosophy best expressed in a handful of phrases: You’re there, we’re here; Go see for yourself; Don’t trust the report.

- There is no problem you can’t solve if you understand your business from A to Z.

- He would try anything, if only for experience.

- The worldview of the immigrant: understanding how so-called garbage might be valued under a different name, seeing nutrition where others saw only waste.

- Because Zemurray discovered a patch of fertile ground previously untilled, his business grew by leaps and bounds.

- The banana business in a nutshell: get big, grow your own, diversify.

- The world is a mere succession of fortunes made and lost, lessons learned and forgotten and learned again.

- There are times when certain cards sit unclaimed in the common pile, when certain properties become available that will never be available again. A good businessman feels these moments like a fall in the barometric pressure. A great businessman is dumb enough to act on them even when he cannot afford to.

- “Sam adapted himself to the ways of life of those he contacted, he became a Hondureño.”

- It does not matter how many bananas you ship: when you lose your reputation, you lose everything.

- Zemurray was the founder, forever on the attack, at work, in progress, growing by trial and error, ready to gamble it all.

- Zemurray was constantly inventing.

- It was always an option: if the leader is in the pocket of the other guy, change the leader.

- Sam was a sharp trader who knew the prize goes to he who does not lose his head or open his mouth too soon. What cannot be accomplished by threats can often be achieved by composure.

- The greatness of Zemurray lies in the fact that he never lost faith in his ability to salvage a situation.

- For every move, there is a countermove. For every disaster, there is a recovery. He never lost faith in his own agency.

- A man focused on the near horizon of cost can lose sight of the far horizon of potential windfall.

- Both sides took the same lesson from the war: compassion is weakness, mercy a disease. You must be willing to go all the way.

- “All we cared about was dividends. Well, we can’t do business that way today. We have learned that what’s best for the countries we operate in is best for the company. Maybe we can’t make the people love us, but we will make ourselves so useful to them that they will want us to stay.”

- Sam’s defining characteristic was his belief in his own agency, his refusal to despair.

What I got out of it

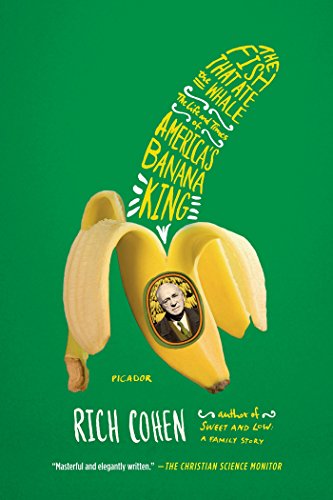

The Fish That Ate The Whale is less a book about Samuel Zemurray, though his entire life gets covered, and more about the banana industry from the late 19th century to the mid 20th century.

I enjoyed learning about Zemurray and the banana industry, but Rich Cohen wanders off frequently both in topic (history of Guatemala and Honduras, Che Guevara) and in writing (“Show me a happy man and I will show you a man who is getting nothing accomplished in this world.”). I especially found the first third of the book tough to get through because of Cohen’s writing.

But there is plenty to learn from Zemurray’s life:

- Immigrant lifestyle and mentality: resourcefulness. One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.

- “Too big to fail” until you are “too big to survive.” When others out-innovate you, death is all but guaranteed.

- Central American history: how the involvement of a massive corporation & US government created the present situation (as a result of the banana trade).

- In the short-term you can survive, grow and thrive as a result of imitation, in the long-term it leads to death. Innovate and thrive; imitate and die.

- Composure and faith in one’s own agency solve a great deal of problems.

- Don’t trust reports; go and see for yourself.

- Summary

- Key Takeaways

- Summary Notes

- Preface

- Selma

- Ripes

- The Fruit Jobber

- Bananas Don’t Grow on Trees

- The Octopus

- The Isthmus

- To the Collins

- Revolutin’!

- To the Isthmus and Back

- The Banana War

- King Fish

- The Fish That Ate The Whale

- Los Pericos

- Bananas Go to War

- Israel Is Real

- Operation Success

- Backlash

- What Remains

- Bay of Pigs

- Fastest Way to the Street

- Epilogue

Summary Notes

Preface

It’s what people mean when they speak of American exceptionalism: unlike the Europeans, we do not yet know you can’t be both powerful and righteous. So we set out again and again, convinced that this time we’ll avoid the mistakes of the previous generations. It’s this kind of confidence that gives people the strength to rule abroad; the moment that confidence goes, the empire is doomed.

Selma

Sam traveled to America with his aunt in 1892. He was to establish himself and send for the others—mother, siblings. He landed in New York, then continued to Selma, Alabama, where his uncle owned a store.

He was fourteen or fifteen, but you would guess him much older. The immigrants of that era could not afford to be children. They had to struggle every minute of every day. By sixteen, he was as hardened as the men in Walker Evans’s photos, a tough operator, a dead-end kid, coolly figuring angles:

Where’s the play? What’s in it for me? His humor was black, his explanations few. He was driven by the same raw energy that has always attracted the most ambitious to America, then pushed them to the head of the crowd.

Over time, Sam would develop a philosophy best expressed in a handful of phrases: You’re there, we’re here; Go see for yourself; Don’t trust the report.

“There is no problem you can’t solve if you understand your business from A to Z” he said later.

He stacked shelves and checked inventory in his uncle’s store. Now and then, he dealt with the salesmen who turned up with sample cases. He stood in the alley, amid the garbage cans and cats, asking about suppliers and costs. There was money to be made, but not here. He interrogated customers. He was looking for different work and would try anything, if only for experience. His early life was a series of adventures, with odd job leading to odd job.

Ripes

In the South, in the days before mechanical equipment, bananas were unloaded by hand, the workers carrying the cargo a stem at a time. A banana stem is the fruit of an entire tree—a hundred pounds or more. Each stem holds perhaps a hundred bunches; each bunch holds perhaps nine hands; each hand holds perhaps fifteen fingers—a finger being a single banana. It was backbreaking work, and dangerous, not just for the shoulders and arms but also for the central nervous system. As any banana cowboy would tell you, banana plants are prized nesting places for scorpions.

Anything can cause a banana to ripen early. If you squeeze a green banana, it will turn in days instead of weeks; ditto if it’s nicked, dented, or banged. A ripe banana will cause those around it to ripen, and those will cause still others to ripen, until an entire boxcar is ruined. Before refrigeration was perfected, as much as 15 percent of an average cargo ended up in the ripe pile.

The worldview of the immigrant: understanding how so-called garbage might be valued under a different name, seeing nutrition where others saw only waste.

Zemurray had stumbled on a niche: ripes, overlooked at the bottom of the trade. It was logistics. Could he move the product faster than the product was ruined by time? This work was nothing but stress, the margins ridiculously small (like counterfeiting dollar bills), but it was a way in. Whereas the big fruit companies monopolized the upper precincts of the industry—you needed capital, railroads, and ships to operate in greens—the world of ripes was wide open.

The Fruit Jobber

He moved to Mobile soon after he went into ripes. Better to live near the docks. Now and then, if business was slow, he took a job. He worked on a ship as part of a cleaning crew, scrubbing decks. He worked in a warehouse as a watchman. I’m not sure where he lived. In a cheap rental in the old part of the city, perhaps; in a boardinghouse by the harbor. He had soon made his name as a uniquely resourceful trader: the crazy Russian who bought the freckled bananas. He was pure hustle.

Because Zemurray discovered a patch of fertile ground previously untilled, his business grew by leaps and bounds.

Selling hundreds of thousands of bananas a year, he’d become one of the biggest traffickers in the trade. And he’d done it without having to incur the traditional costs. His fruit was grown for him, harvested, and shipped for free.

Bananas Don’t Grow on Trees

A banana plant, under the best conditions, can grow twenty inches in twenty-four hours. The thought can make you sick: groves of stems and monstrous leaves expanding while we sleep, desiring, it seems, to cover completely the sunny parts of the world. Which, of course, makes it an ideal crop for a businessman. It’s never out of season. A single plant can bear fruit as many as three times a year for twenty years or more. And when the stem is finally kaput, and by now you’re old and rich, you dig up the rhizome, hack it to pieces, plant each piece, and watch those grow. Thus another twenty years go by.

Some facts about the banana:

- It’s not a tree. It’s an herb, the world’s tallest grass. Reaching, in perfect conditions, thirty feet, it’s the largest plant in the world without a woody trunk.

- Its stem actually consists of banana leaves, big, thick elephant ears, coiled like a roll of dollar bills. As the plant grows, the stem uncoils, revealing new leaves, tender at first, rough at last.

- The fruit appears at the end of a cycle, growing from a stem that bends toward the ground under its own weight.

- Because the plant is an herb, not a tree, the banana is properly classed as a berry.

- The plant grows from a rhizome, which, in the way of a potato, has no roots. It’s outrageously top-heavy and can be felled, as entire fields sometimes are, by a strong wind.

- Though the plant can be grown all over the world, it will, with two exceptions, bear fruit only in the tropics.

- Iceland and Israel are the exceptions: Iceland because it grows on the slopes of a volcano; Israel for reasons that remain mysterious. Various attempts to farm bananas commercially in the continental United States—California, Louisiana, Mississippi, southern Florida—have failed.

- The tree bears a red flower, a delicate, bloody thing, a few days before it fruits.

- The banana’s great strength as a crop is also its weakness: it does not grow from a seed but from a cutting. When the rhizome is chopped into pieces and planted, each piece produces a tree.

Like most booms, it could not last. Not because there was anything wrong with the product: the banana is perfect. Not because there was any scarcity in demand: people loved bananas from the start—the average American now consumes seventy a year. But because supply was uncertain. The banana, as I’ve said, is terribly vulnerable: to wind, cold, heat, rain, lack of rain, flood, disease.

Most firms got their fruit from a single farm or valley, greatly increasing this vulnerability. The entire supply of many early traders could be wiped out by one bad storm. This became painfully clear in 1899, the Year Without Bananas.

There had been a heat wave, a flood, a drought, a hurricane. The market sheds were shuttered, the pushcarts stood empty. Dozens of firms went under. It was like the natural disaster that wipes out all but a few impossible-to-kill species.

The handful that did survive came away smarter, having learned basic lessons that would dictate how the business was organized in the future:

- Get big – A banana company needs to be fat enough, with enough capital in reserve, to weather inevitable freak occurrences, such as an earthquake or a hurricane.

- Grow your own – A banana company needs its own fields so it can control planting and harvesting, thus avoiding ruinous competition in the event of a down season.

- Diversify – A banana company needs plantations scattered across a vast terrain, stems growing in far-flung countries, so that a disaster that wipes out the crop of a particular region will not destroy the firm’s entire supply.

If you study these lessons, you will understand the development of the banana business, how it grew from mom-and-pop trading posts into an all-powerful behemoth.

The world is a mere succession of fortunes made and lost, lessons learned and forgotten and learned again.

The Octopus

He developed a routine: bananas in summer, mackerel in winter, oysters in spring. In July 1871, he sailed into Boston with the biggest load of bananas the city had ever seen.

Andrew Preston was on the docks the afternoon that load came in. A buyer for Seaverns & Morrison, a Boston produce dealer, Preston took a special interest in perishables. He made a career of recognizing a prize at a distance. He got his hands on everything: pineapples, persimmons, pomegranates.

For years, the men had an informal arrangement: Baker carried the bananas to Preston, who sold them across an ever-expanding territory. Preston meant to change the model of the business. It had been low volume, high price; he would make it high volume, with cheap bananas sold up and down the economic scale.

To achieve this, Baker and Preston had to increase supply and control quality. In the early days, Baker carried whatever happened to be available—the Cavendish, the Lady Finger, the Jamaican Red. In the future, he would ship only the Big Mike: a buyer has to know what he’s going to get. The Big Mike had the advantage of being tough—stack it and it will not bruise.

There were two ways for the company to grow:

- Preston could scout property, plant fields, and harvest bananas,

- or he could find someone who had done these things already.

Keith thought bananas would serve as a cheap food for his own workers, but soon realized, as Frank had before him, that there was a tremendous market for bananas in the North. He formed the Tropical Trading and Transport Company to carry his fruit but sold most of his crop to other suppliers. Though he considered himself a railroad man—it was his dream to build a train from New York to Tierra del Fuego—his business was supported by bananas.

The company still held 184,000 unsold shares. With this in hand, Preston put the second part of the plan into effect—a cunning way to bring order to a chaotic industry. He traveled from port to port, stopping in every city where bananas moved in numbers. He took aside dozens of importers and jobbers, giving each the same pitch: join us; get big; survive. In return for shares in their small companies, these men would receive United Fruit stock

This was the age of trusts, when steel and oil concerns combined to monopolize their industries. It was also the age of trustbusters, when the government went after any would-be Rockefeller who tried to get a stranglehold on a trade. (The Sherman AntiTrust Act passed in 1890.) With this in mind, Preston was careful to control no more than 49 percent of the business in any market. He wanted to get big enough to dominate but stay small enough to avoid prosecution. The independents who survived this wave—a tidal wave that remade everything that came before—were allowed to survive by United Fruit.

They were left to stand as proof of healthy competition. In other words, even its rivals existed so U.F. could prosper.

The company solidified its control by amassing the Great White Fleet, the ships that ruled the Caribbean. Within a decade, the fleet—each vessel painted white to reflect the tropical sun—was carrying not just bananas but also the mail and cargo of Central America. In the case of a strike or disagreement, the company could simply shut down the commerce of the region.

By 1905, the banana trade was United Fruit. The company owned the most ships, planted the most fields, had the most money, and controlled both supply and demand: supply by planting more or less rhizomes, demand by increasing the market. Beginning around this time, U.F. stationed an agent at South Ferry terminal in New York, where the Ellis Island Ferry landed. Handing a banana to each immigrant who came off the boats, the agent said, “Welcome to America!” This was to associate the banana with the nation, a delicacy of the New World.

At the same time, U.F. began selling baby food made from bananas, which would hook customers when they were tiny. In 1920, the company introduced a hot banana drink meant to take the place of coffee—it failed. There was banana flour and banana bread. In 1924, U.F. published a book of recipes meant to jack up sales.

Each of these efforts associated the banana with the beginning—of your life, of your day, of your career as an American. In this way, the banana, which had been exotic, was turned into a staple, the most familiar, necessary, obvious thing in the world. In this way, business boomed.

United Fruit dealt with its competition in one of two ways: absorb or crush.

In 1909, the case reached the Supreme Court. It’s interesting to consider what might have happened if the Justice Department had won its case against United Fruit as it won its case against Standard Oil two years later. If U.F. had been broken up, if the monster had been divided into a half dozen little monsters, American history in Latin America might have been very different. An isthmus without El Pulpo is an isthmus in which the United States is not demonized in the same way.

By growing its product there and selling it here, U.F. had stumbled on the greatest tax-saving, law-avoiding scheme of all time. With this decision, Justice Holmes cleared the way for that crucial player of the modern age: the global corporation that exists both inside and outside American law, that is everywhere and nowhere, and never dies.

The Isthmus

There are times when certain cards sit unclaimed in the common pile, when certain properties become available that will never be available again. A good businessman feels these moments like a fall in the barometric pressure. A great businessman is dumb enough to act on them even when he cannot afford to.

To the Collins

“Sam adapted himself to the ways of life of those he contacted,” Fortune reported. “He cultivated friendship, and did not scorn to take a drink with the peasants. He acquired a wonderful command of their language [sic], including swear words, which he didn’t hesitate to employ. He became a Hondureño.”

In setting a price for the property, Zemurray took advantage of the local landowners. He had superior information, understood something important lost on the Hondurans. To the peasants, the land was swamp and disease, nothing that will still be nothing in a hundred years. Sam knew better. Because he was raised on a farm, he realized the meaning of all that black soil beneath the weeds. Because he worked as a jobber, he realized the worth of the fruit that would thrive in that soil. This land, picked up for a song, was in fact the most valuable banana country in the world.

He believed in the transcendent power of physical labor—that a man can free his soul only by exhausting his body.

Revolutin’!

In a strange way, the seizure, which would have been helpful to President Dávila a week earlier, hurt him now. Having established a base in Trujillo, the insurgents no longer needed the Hornet. But its seizure made it look to Hondurans like the United States was intervening in a civil war on the side of the government. It was a feat of propaganda: Bonilla and Christmas, working with Zemurray, were able to frame the war as an insurgency, the people rising up against a government selling the nation to gringos and Yankee bankers, whereas what you really had was more sinister and interesting—a battle waged by a private American citizen, a corporate chief, against a debt-ridden but sovereign nation.

By financing the overthrow of Dávila, Zemurray did more than relieve himself of taxes and duties: he entered his name in the black book of Latin American history. He had taken ownership of a nation, whether he realized it or not. As Kinzer explained, “No American businessman ever held a foreign nation’s destiny so completely in his hands.” Over time, Zemurray would become more powerful than even the government of Honduras. When that happened, the people would begin to look to him to supply the sort of services usually supplied by the state: water, health, security, etc., things it would prove impossible to deliver. Every great victory carries the seed of ultimate defeat.

To the Isthmus and Back

Everywhere workers gathered, bloodied by the police, beaten but not defeated, they attached their misery to the name on the side of the boats carrying away the product of their labor: Cuyamel. It damaged Sam’s name in a country where he’d long been admired as the son-in-law of the beloved Parrot King. Zemurray never forgot the lesson. It does not matter how many bananas you ship: when you lose your reputation, you lose everything.

Unlike other bosses, Zemurray lived in the jungle with his workers, spoke their language, knew what they wanted and what scared them. (As Zemurray liked to say, “You’re there, we’re here.”) It’s why he was hated and why he was loved. Because he was a person and a person you can disagree with and be angry at but still admire, whereas United Fruit was faceless in a way that terrifies.

It was about profit margin, the efficiency of trade, the morale and skill of the employees. It was increasingly clear: Samuel Zemurray had built the better business.

Cuyamel was superior to United Fruit in a dozen ways that did not show up on a balance sheet. U.F. was a conglomerate, a collection of firms bought up and slapped together. There was a lot of redundancy, duplication of tasks, divisions working against divisions, rivalries, confusing chains of command. Cuyamel Fruit was the Green Bay Packers by comparison. Every decision was made with confidence and authority. Zemurray could move without waiting for permission or a committee report.

It was a contrast of styles: the executives who ran United Fruit had taken over from the founders and were less interested in risking than in preserving. Zemurray was the founder, forever on the attack, at work, in progress, growing by trial and error, ready to gamble it all.

The difference was best seen on the plantations, where Zemurray was constantly inventing. Most people, looking at a banana, see a delicious fruit. When Zemurray looked at a banana, he saw room for improvement. He innovated banana farming, which had not changed since the first days of the trade, in the following ways:

- Selective pruning – His men walked the fields, ripping out runts and dwarfs, which was seen by some as madness.

- Drainage – Most banana plantations were built in river valleys, which offered natural drainage. Zemurray augmented this with spillways and canals, making good drainage better.

- Silting – United Fruit built levees to prevent its fields from flooding. Zemurray allowed certain fields to be inundated, resulting in an accretion of silt, an excellent fertilizer.

- Staking – At Cuyamel, each tree was tied to a length of bamboo, which protected stems against high winds and kept them on the straight and narrow.

- Overhead irrigation – Traditional banana men considered watering a waste of resources, since the sky delivered two hundred inches of rain a year. Zemurray argued that, as all that rain was not evenly distributed, with the wet season followed by two months of scorchers, the sky could use some help. He filled fields with overhead sprinklers that mimicked the fall of rain and went on with a click. The result was banana plants exploding with bunches, each filled with the fattest fingers anyone had ever seen. It was not a matter of measurements: you could tell just by looking.

The Banana War

From the outside, the Banana War seems unfathomable. Zemurray had taken on an enemy of superior resources and size over a few thousand acres that could add only marginally to his wealth. Why did he do it? Why didn’t he strike a deal? To understand this, you have to understand Zemurray’s personality— personality and style being the great unaccounted factors in history. Strength, charisma, shrewdness, power—his defining characteristics were the sort not recorded in photos or articles, which can make him seem mysterious, strange. What drove him? Didn’t he know you can’t take it with you in the end? (Yes, but this is not the end.) To colleagues like Frank Brogan who knew Zemurray, his motivation was clear: he wanted to win. And would do whatever it took. Here was a self-made man, filled with the most dangerous kind of confidence: he had done it before and believed he could do it again.

When this mess of deeds came to light, United Fruit did what big bureaucracy-heavy companies always do: hired lawyers and investigators to search every file for the identity of the true owner. This took months. In the meantime, Zemurray, meeting separately with each claimant, simply bought the land from them both. He bought it twice—paid a little more, yes, but if you factor in the cost of all those lawyers, probably still spent less than U.F. and came away with the prize.

It was always an option: if the leader is in the pocket of the other guy, change the leader. This was a preferred Zemurray tactic: if you meet a truly formidable foe, flip him.

When Zemurray realized he would never get permission to bridge the Utila, he did what he’d always done: innovated, building surreally long docks on both sides of the river, then having his engineers design a temporary bridge, though no one was allowed to call it that. The inflatable device could be thrown from extended dock to extended dock in no time, completing the railroad that ended on one pier and began again on the other.

Sam was a sharp trader who knew the prize goes to he who does not lose his head or open his mouth too soon. What cannot be accomplished by threats can often be achieved by composure. Sit and stare and let your opponent fill the silence with his own demons.

Whereas the young Sam was reckless and immune—from nowhere, with nothing—there were all sorts of ways the middle-aged Sam could be hurt. Success limited his options and made him vulnerable.

King Fish

Zemurray was, in important ways, as Jewish as can be. His philanthropy was an example: it was not how much he gave, it was the way he gave. He seemed to be aware of the concept of tzedakah, the obligation to give as spelled out in Deuteronomy and explained in the Deuteronomic Code—a man needs a code or else lives willy-nilly, like an animal —which requires tzedakah from every Jew, even the struggling. If you have a little more than nothing, divide that little more into ten parts and give one away.

The Fish That Ate The Whale

The greatness of Zemurray lies in the fact that he never lost faith in his ability to salvage a situation.

When the secretary of state teamed up with J. P. Morgan and the Honduran government in a way contrary to Zemurray’s interests, he simply changed the Honduran government. When United Fruit drew a line at the Utila River and said, “You shall not cross,” he crossed anyway. When he was forbidden to build a bridge, he built a bridge but called it something else. For every move, there is a countermove. For every disaster, there is a recovery. He never lost faith in his own agency.

He started by asking two questions.

- Are the challenges facing United Fruit part of the systemic failure of the global economy, meaning there’s nothing to do but hope and pray?

- If the answer to the first question is no, what can be done to move the product, increase profits, resuscitate the company? How can U.F. be saved?

Where did Zemurray go for answers? Did he meet with economic experts and college professors? Did he call Daniel Wing, the chairman of U.F.’s board, and Victor Cutter, its president, and ask, “Do you have a plan?” And even if they did have a plan, so what? These were the same men who had run the company into a ditch. He went to the docks instead, where he spent the winter of 1932 walking through warehouses and standing on the decks of banana boats, talking to fruit peddlers and captains, loaders and stevedores—the people who really knew.

A man focused on the near horizon of cost can lose sight of the far horizon of potential windfall.

The best tycoons are like magicians; they know when to share information and when to withhold.

Los Pericos

“I realized that the greatest mistake the United Fruit management had made was to assume it could run its activities in many tropical countries from an office on the 10th floor of a Boston office building,” Zemurray told Fortune. “The management had tried to tell every executive in every country exactly what he must do and how he must do it. Executives on the spot were treated like messenger boys. I completely reversed that policy. I laid down what might be called a constitution for the company. This constitution provided for a maximum of home rule in the field. It was established as a fixed policy that if [a plantation manager] could not handle his difficulties reasonably satisfactorily, we would appoint some man who could.”

He left fields fallow, further decreasing banana supply, controlling market price. On some plantations, he replaced bananas with sugarcane, a staple always in demand. Realizing the company had become overly dependent on a single product, he looked for other crops to plant: coconuts, pineapples, quinine trees.

Every banana is a clone, in other words, a replica of an ur-banana that weighed on its stalk the first morning of man. This has been the strength of the industry, and its weakness. The strength because talk about quality control! The weakness because the lack of diversity puts each banana species at risk. Given the opportunity, a disease that kills one Big Mike is going to kill them all.

Bananas Go to War

What do you do when your product rots? Find something else to sell. United Fruit still had acres of sugarcane scattered across the Caribbean, which continued to be profitable, but it was not nearly enough. Zemurray began to look for other crops he could grow on his plantations, crops that could be classified as necessities (no quota).

By 1944, Zemurray had thousands of acres bearing strange fruit. As he later told reporters and friends, it was among the proudest achievements of his life. He was a farmer at heart. And here he was behaving like a farmer in the midst of a locust blight, innovating his way out of ruin.

Israel Is Real

It’s the one problem he could never solve: having designed a uniquely powerful position for himself at the top of the company, tailored to his character and style, Zemurray could not find anyone else to fill it.

Operation Success

Where did the interest of United Fruit end and the interest of the United States begin? It was impossible to tell. That was the point of all Sam’s hires: If I can perfectly align the interests of my company with the interests of top officials in the U.S. government—not the interests of the country, but the interests of the people in charge of the country—then the United States will secure my needs.

Edward Bernays, the man who invented modern public relations. Bernays approached the age of mass media like a scientist in search of general principles.

He had two basic insights from which everything else followed:

- Modern society, with its millions, is essentially ungovernable. The public must instead be controlled by manipulation. The men who do this manipulating, in government or not, are the true leaders, philosopher-kings. They need not manipulate all the people, only the few thousand who set the agenda. The drivers of history are not the people, in other words, nor the elite who influence the people, but the PR men who influence the elite who influence the people. “Those who manipulate [the] unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power,” wrote Bernays. “We are governed, our minds molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.”

- The people can be made to behave as you want them to behave via the subconscious of the public mind—no one else believed such a thing existed— which can be directed with symbols and signs. “If we understand the mechanism and motives of the group mind,” asked Bernays, “is it not possible to control and regiment the masses according to our will without their knowing about it?”

He described his grand strategy as indirection. If General Motors hired Joe Schmo to sell cars, Joe Schmo would give an interview to Road & Track, telling them the specs of the Thunderbird, engine size in cubic inches, zero-to-sixty, and so on. Given the same job, Bernays would lobby Congress for higher speed limits, making it more fun to own a Thunderbird.

Rather than fight for a single season of sales, he would make the world more friendly to his product. In the 1950s, a consortium of publishers—including Harcourt Brace and Simon & Schuster—concerned about a dip in numbers, hired Bernays. Did he go into schools and make the case for books? No, he talked to the architects and contractors who were designing the new suburban homes and convinced them a house is not modern if it does not include built-in bookshelves.

Who was Edward Bernays’s real audience? Whom did he need to sell? It was, in my opinion, less the American people than the American government, and less the American government than a handful of men working for the CIA.

Rarely does a skirmish end so decisively, with the disputed issues resolved in such a satisfactory fashion. It was the most lopsided victory in the history of United Fruit. Too lopsided. Did Zemurray realize the danger his company faced, not as a result of its losses but as a result of its wins?

Sam should have known, must have known. The coup in Guatemala violated a rule he had practiced all his life: do not draw unnecessary attention.

Both sides took the same lesson from the war: compassion is weakness, mercy a disease. You must be willing to go all the way.

Backlash

Was Eisenhower punishing United Fruit for duping him, or was he sacrificing the company with his own reelection in mind? To know this, you must determine the following: Who was in control in Guatemala? Had United Fruit manipulated the CIA, or had the company been used—a tool in a cold war? Most historians long believed the coup was staged at the behest of the company, as it was no longer politically feasible for the banana men to field a mercenary army of their own. But some suggest the trickery went the other way.

What Remains

“All we cared about was dividends. Well, we can’t do business that way today.

We have learned that what’s best for the countries we operate in is best for the company. Maybe we can’t make the people love us, but we will make ourselves so useful to them that they will want us to stay.”

Sam Zemurray’s life is the true story of the American dream—not only of the success but of the price paid for the ambition that led to that success.

Bay of Pigs

A corporation is a product of a particular place and a particular time. U.S. Steel was Pennsylvania in the 1890s. Microsoft was Seattle in the 1980s. It’s where and when their sense of the world was fixed. United Fruit/Cuyamel was a product of Central America circa 1911. It was a kingdom that ended in the way of the British Empire, slowly, then all at once. Everyone came, then everyone left.

Fastest Way to the Street

In the 1950s, Standard Fruit introduced the banana box. I don’t want to talk too much about this—a box is a box—but it was a revolutionary development in the trade. It changed the way bananas were sorted, stacked, and shipped. Not inventing the banana box was an embarrassment for U.F. The company had lost its edge. “In place of the innovations that marked its early years, the character of the company became imitative,” explained Thomas McCann. “It merely repeated earlier moves and tactics. The company had lost every semblance of invention. In the areas of production, sales and transportation, as in politics, United Fruit was doing business at the same old stand, but in fifty years the neighborhood had changed beyond recognition.”

Epilogue

As long as you’re breathing, the end remains to be written.

Sam’s defining characteristic was his belief in his own agency, his refusal to despair. No story is without the possibility of redemption; with cleverness and hustle, the worst can be overcome.